Reviewed by Martina Thiele

The sudden and much too early death of communication researcher, publicist, documentary filmmaker and media critic Lutz Hachmeister in 2024 not only shocked those who knew him personally. Many obituaries stated that »we«, German society, urgently needed critical scholars like him »especially in these times«. Especially, I would like to add, as his analyses of the present were always based on a profound knowledge of history. This is also evident in his last book, which was published shortly after his death in the fall of 2024. Hitler’s Interviews: The Dictator and the Journalists offers a comprehensive analysis of the more than 100 interviews that Adolf Hitler gave to foreign journalists and a few women journalists[1] between 1922 and 1944.

The sudden and much too early death of communication researcher, publicist, documentary filmmaker and media critic Lutz Hachmeister in 2024 not only shocked those who knew him personally. Many obituaries stated that »we«, German society, urgently needed critical scholars like him »especially in these times«. Especially, I would like to add, as his analyses of the present were always based on a profound knowledge of history. This is also evident in his last book, which was published shortly after his death in the fall of 2024. Hitler’s Interviews: The Dictator and the Journalists offers a comprehensive analysis of the more than 100 interviews that Adolf Hitler gave to foreign journalists and a few women journalists[1] between 1922 and 1944.

Lutz Hachmeister examines how Hitler and his aides in the Foreign and Propaganda Ministries strategically used these interviews to spread National Socialist ideology, but also for day-to-day political purposes. US, British, Italian and French journalists in particular had the chance to talk to Hitler if they submitted their questions in advance. After the interview, the text had to be submitted again and approved. For journalists, an interview with Hitler was a scoop due to the worldwide interest in the political situation in Germany. However, Hitler was not an easy interviewee. As Hearst journalist Karl von Wiegand noted: »I didn’t get anything out of him. If you ask him a question, he makes a speech. This whole visit with him was a waste of time.« (p. 11) Nevertheless, Wiegand conducted further interviews with Hitler afterwards, and Sefton Welmer from the London Daily Express and Louis P. Lochner from the Associated Press news agency also interviewed Hitler several times. Hitler hardly gave any interviews to German newspapers, either before 1933 or afterwards. Of course, after The Nazis came to power, the domestic press, which had been brought into line, regularly reported on the great interest »abroad« in National Socialist Germany and referred to the interviews with the »Führer«.

Lutz Hachmeister begins with a prologue in which he explains how Hitler talked his way to power. His »non-stop suada, his persistent monologuing in all kinds of communication situations« was also evident in the interviews – which are actually a dialogical form. Hachmeister divides them into three phases: early interviews, which lasted until the arrest of the »Bavarian Mussolini« after the 1923 coup attempt and his imprisonment in Landsberg; then the rise to power between 1930 and 1933, when the National Socialists gained ground in elections, and finally the phase of dictatorial power between 1933 and 1945, when Hitler was head of state and commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht. In this prologue, Hachmeister discusses in detail the many Hitler biographies, which ultimately offer little that is new. He points out the analytical limitations of skewed »Weimar reloaded analogies«, deals with the meaning and purpose of the journalistic genre of interviews, and adresses the current debate about interviewers as »useful idiots« who offer right-wing extremists a platform for self-promotion. The author returns to these questions in the epilogue, but already teases: »Interviews with dictators and autocrats make little sense.« (p. 39)

In the following chapter, Hachmeister focuses »the apparatus«, Hitler’s helpers who organized the interviews. It is entitled »Putzi and Charlie«. This refers to Franz Sedgwick Hanfstaengl, the first »foreign press officer of the NSDAP« and newspaper researcher Prof. Dr. Karl Böhmer, both from middle-class families, with contacts in the US, sophisticated and well-connected. Hachmeister describes in a knowledgeable and thoroughly entertaining way how successful their Nazi careers were, then ended abruptly and, in Böhmer’s case, fatally due to his talkativeness while drunk. The rivalry between the Nazi public relations officers in the Foreign Office and those in the Ministry of Propaganda, who obstructed and denounced each other, becomes clear. Hachmeister also refers to those who were able to continue their careers in West Germany after 1945 without being bothered.

In the following chapters, the author focuses on the US, French and British interviews. He then turns to the interviews with »Axis journalists« and »neutrals«, because Italian and Japanese journalists in particular were also eager stenotypists and, like Dottore Leo Negrelli, convinced fascists. In a conversation with him in 1923, Hitler rambled on about »the struggle of the Jewish-Marxist principle against the principle of nationalities« (p. 207). Negrelli became Hermann Göring’s liaison in Italy and in 1926 editor-in-chief of the German-language Alpenzeitung in Bolzano, which promoted the fascization of South Tyrol through its journalism.

The wealth of meticulously documented detailed information on individual persons, their networks, and careers, and the easily readable presentation of this diverse information set Hachmeister’s study apart from from the mass of books on the Nazi state, Hitler, and his vassals. Hachmeister is too familiar with the historical controversies between »intentionalists« and »structuralists« to take sides. Why should he, when only a holistic view promises new insights? In the chapter »Faking Hitler«, the author focuses on interviews with Hitler that are very likely fabricated and casts doubt on the authenticity of the interviews conducted by Catalan journalists Josep Pla and Eugeni Xammar in 1923.

The book concludes with a chapter on the Hitler interview conducted by US diplomat John Cudahy in 1941, which contemporaries such as the US Secretary of the Interior Harald L. Lickes criticized in the New York Times as a complete failure. Lickes describes the interviewer John Cudahy, »our former ambassador to Belgium«, as a »simple fellow« who unfortunately allowed Hitler to cloud his mind (p. 259).

For their meticulous analysis of the conversations with Hitler, Hachmeister and his team, whom he expressly thanks, were unable to draw on audio recordings or original manuscripts, only on the interviews published in the press. What was actually asked and answered is therefore not documented. Nor is it possible to determine what changes had to be made before the interview was accepted. Unfortunately, there are no reproductions of the interviews. At least a press clipping would have been informative, and not just for media scholars. However, there are some photos in the volume as well as an extensive index of names, numerous notes and cross-references and at least the chronologically ordered list of interviews in the appendix.

In the epilogue, Hachmeister takes up the introductory question »How do you interview a dictator – and why at all?« and speaks of »Hitler as a cipher for journalism research«, because »these questions apply to all dictators and autocrats.« (p. 281) Hachmeister offers a topical all-round review and does not hold back with assessments of more or less successful interviews that journalists have conducted with Vladimir Putin, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Fidel Castro, Denk Xiaoping, Henry Kissinger and many more. Those who are less interested in detailed historical knowledge than in the current dos and don’ts of the revived »dictator interview« genre will prefer this epilogue to the middle section of the book. However, those who lean toward a genealogical understanding of history must read the entire book as an incredibly rich archive and legacy – and praise it.

About the reviewer

Martina Thiele, Dr. disc. pol., is Professor of Media Studies at the University of Tübingen. Her research and teaching focuses on digitalization and social responsibility, media and public sphere theories, gender media studies, and stereotype and prejudice research. She is one of the editors of Journalism Research. Contact: martina.thiele@uni-tuebingen.de

Footnote

1 The »List of Interviews« (from p. 337) shows that Annetta Halliday-Antona, Detroit News; Dorothy Thompson, Hearst’s International Cosmopolitan; Anne O’Hare McCormick, The New York Times; Élisabeth Sauvy, Paris Soir; Inga Arvad, Belingske Aftenavis interviewed Hitler. Hachmeister is pleased to highlight Sigrid Schultz, a journalist who did not interview Hitler, but who knew him personally as head of the Chicago Tribune’s Berlin bureau. Schultz was committed and courageous in representing the interests of foreign reporters against the Nazi censors. She refused an exclusive interview with Hitler, among other things, because »10 cents per Hitler word were demanded« (see p. 101).

About the book

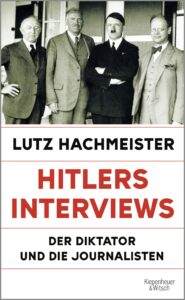

Hachmeister, Lutz (2024): Hitlers Interviews. Der Diktator und die Journalisten [Hitler’s interviews. The dictator and the journalists]. Cologne: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 379 pages, EUR 28

![Hachmeister, Lutz (2024): Hitlers Interviews. Der Diktator und die Journalisten [Hitler’s interviews. The dictator and the journalists]](https://journalistik.online/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/cropped-journalistik-hintergrund-groß.png)