By Roxane Biller, Seraina Cadonau and Marion Frank

Abstract: Diverse and sensitive journalistic reporting is only possible where there is a diversity of staff in editorial offices. Previous studies (cf. e.g., Niggemeier 2018; Hasebrink et al. 2021; Spiller 2018) demonstrate the relevance of the topic. The question guiding the research behind this paper is whether the composition of newspaper editorial offices is sufficiently diverse to reflect the population as a whole. The focus is on three characteristics of diversity: gender, age, and origin. The authors are also interested in the differences between newspapers of different political orientations and between the levels of editorial office and leadership positions. A total of 1,503 data sets from six editorial offices of national newspapers, collected from publicly accessible secondary data and from primary data requested personally, were analyzed. The analysis shows that young people, people with a history of immigration, and women are under-represented in German newspaper journalism. Connections were found between the political orientation and the origin of the staff, and between the hierarchical level and the age structure. Consequently, German newspaper editorial offices do not currently have sufficient diversity among their staff.

Keywords: diversity, newspaper journalism, gender, age, origin

In democratic societies, the role of journalism is to provide complete, objective, comprehensible information in order to enable different recipients to weigh arguments independently and form opinions freely (cf. Neuberger/Kapern 2013: 81; Wellbrock/Klein 2014: 407). Furthermore, journalism needs to critique, scrutinize, educate, and entertain. The value of journalistic work for democracy relies on adherence to journalistic quality. Wellbrock and Klein’s (2014) criteria for journalistic quality include topicality, relevance, accuracy, truthfulness, transparency, ethics, and legality (cf. Wellbrock/Klein 2014: 391). When it comes to questions of ethics and relevance, the only way to guarantee objectivity is through a diversity of perspectives. Furthermore, cultural and social differences can be illustrated by empathetically depicting the different living situations and ways of life of individual groups in society (cf. Hasebrink 2016: n.p.). Up to now, stereotypical images, for example of migrants, have dominated in daily newspapers (cf. Lünenborg et al. 2011: 104-106). But journalism needs diversity in order to cover and address the full spectrum of lived realities. It holds up a mirror to society and acts as a mediator between the classes and flows. Addressing the definition of diversity is essential in order to maintain a diversity of perspectives and to prevent prejudice and discrimination.

The central research question is: To what extent are the characteristics gender, age, and origin distributed among journalists in German newspaper editorial offices in a way that fairly reflects diversity?

This guiding question was used as the basis to derive two sub-questions and hypotheses, in order to examine potential connections with the political orientation of a newspaper and the hierarchical level.

»Diversity« refers to the distinctness and variety of individuals within groups (cf. Hanappi-Egger 2012: 178; Harrison/Sin 2006: 191ff.), and can be investigated using various social categories such as gender identity, age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and religion (cf. Hanappi-Egger 2012: 178). Intended to make diversity in an organization tangible, the diversity model of the Diversity Charter[1] (2021a) contains seven core dimensions, as well as external and organizational dimensions. These dimensions were developed based on the work of Gardenswartz and Rowe (1994) and adapted to current conditions. The most important are age, gender and gender identity (gender), and ethnic origin and nationality (origin) (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 6). The characteristics most closely linked to an individual’s personality, they were selected for this study because they are likely to be handled very transparently and are therefore the most likely to permit complete data collection. The other core dimensions are physical and mental abilities, religion and worldview, sexual orientation, and social origin (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 6).

This work is based on data collected on diversity in German newspaper journalism (n = 1503) in 2021. The data comprises both secondary data on employees of newspaper editorial offices accessible online, and primary data directly requested. Statistical methods such as a chi-squared test and a Levene’s test were used for data analysis.

Diversity in journalism: current status of research

The book by Hanitzsch, Seethaler and Wyss analyzed data from 2,502 journalists from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (cf. Hanitzsch et al. 2019: 20). The proportion of women in the German sample was 40% – a slight rise compared to a study from 2005 (cf. Dietrich-Gsenger/Seethaler 2019: 53f.), in which the proportion of women was 37% (cf. Weischenberg et al. 2006: 268). Women with more than 15 years of professional experience made up just 30% of the German sample (cf. Dietrich-Gsenger/Seethaler 2019: 58). The men journalists had an average of 22 years of experience, the women journalists just 16 – regardless of the media genre (cf. Dietrich-Gsenger/Seethaler 2019: 59). Looking at the hierarchical level, Dietrich-Gsenger and Seethaler (2019: 53) noticed that women held only around a fifth of the leadership positions, such as editor in chief or a similar function. The lowest proportion of women, 31.7%, was seen in newspaper editorial offices. 48.7% stated that they worked for magazines, and 50% said they were employed in online editorial offices (cf. Dietrich-Gsenger/Seethaler 2019: 55).

The average age of the German sample at the time of the survey was 46 years (cf. Dietrich-Gsenger/Seethaler 2019: 57), having been just 41 in 2005 (cf. Weischenberg et al. 2006: 268). In the German sample, journalists aged 29 and under were the least represented, accounting for 7%. Respondents from the 50+ age group were most strongly represented, at 40% (cf. Dietrich-Gsenger/Seethaler 2019: 57). There was also a discernable age difference between men and women. The women German respondents were around 4.5 years younger on average than their men colleagues. The study by Dietrich-Gsenger and Seethaler (2019: 58) also showed a slight increase in women, especially in the 26 to 35 years age group. In the higher age groups, the low proportion of women remained unchanged.

ProQuote[2] investigates the gender distribution in journalistic leadership positions at regular intervals, referring to a single media segment in each case, such as newspapers. The study from 2019 shows that the proportion of women in the position of editor in chief or deputy editor in chief at regional newspapers is just 11.7% (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 9). Of these, women are more likely to hold the position of deputy, while three of the eight women editors in chief share the position with a man colleague. As a result, just five of the 100 newspapers in the ProQuote sample had a woman as sole editor in chief (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 9). ProQuote had conducted the same investigation in 2016, and was able to detect a slight increase in the proportion of women as editors in chief between 2016 and 2019 (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 11). In addition, ProQuote investigated the gender distribution at the leadership level of national newspapers, taking their political orientation into account (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 66f.). The results clearly showed that only the left-wing alternative newspaper die tageszeitung taz employed equal numbers of women and men in leadership positions in 2019 (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 18). They were followed by other left-wing liberal newspapers: Süddeutsche Zeitung and Die Zeit (cf. Käppner/Mayer 2020: n.p.). Tabloid newspaper Bild had women in just 27.7% of leadership positions – less than a third. At the two bourgeois-conservative newspapers Die Welt and FAZ, only around 20% of leading staff were women. Economic newspaper Handelsblatt came in last place in the investigation (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 18).

A study conducted in 2020 by the association Neue deutsche Medienmacher:innen made important findings regarding origin. The investigation by Boytchev et al. shows that journalists with a background of migration are under-represented. Of the 126 editors in chief surveyed, 118 were German with no background of migration. Just eight respondents had a background of migration, none of them from outside Europe (cf. Boytchev et al. 2020: 9f.). The results of the study also show that German media houses were not clear about the diversity of their journalists at the time of the investigation. Of the 122 editorial offices surveyed, just 56 responded to the question of whether they knew the proportion of journalists in their editorial office with a background of migration. None (except one) was able to provide reliable, systematic information (cf. Boytchev et al. 2020: 10). News agency Thomson Reuters is the only one to record the citizenship of its staff for the purpose of statistical analysis. The proportion of employees with a background of migration there was 31%, presumably due to the agency’s multinational status (cf. Boytchev et al. 2020: 11).

Looking at the various studies, the shortage of specific, current figures is striking. It is impossible to gain a reliable picture of journalists in editorial offices and at leadership levels. The study by Hanitzsch et al. (2019), described above, makes it possible to draw some systematic conclusions on gender and age, but its data collection stems from 2015 and is thus no longer up to date. The sample in that study is also very small. Moreover, it is clear that there are fewer studies on origin and age in the media sector than on gender. Up to now, few studies have focused on the diversity of conventional newspaper editorial offices. The ProQuote study did examine the medium of newspapers, but only looked at the gender ratio at leadership level.

Due to the lack of data, potential connections with factors such as the political orientation of a newspaper remain unclear. This paper hopes to close this research gap by investigating the diversity of newspaper journalism in Germany based on the three characteristics gender, age, and origin. The diversity characteristic gender takes the binary gender options into account; the age is recorded in years; the origin category is defined by nationality.

We take a diversity-oriented gender distribution to mean as balanced a ratio as possible between men and women. For the age characteristic, diversity would mean that the age distribution in the editorial offices corresponded to that of the total population of adults subject to social insurance contributions. For the purposes of this paper, the origin characteristic would be appropriately diverse if the proportion of colleagues among all journalists were similar to the proportion of those of foreign nationality in the total population.

The question guiding the research covers not only journalists with editorial roles but also those in leadership positions, as these have a key influence over which content is published and which topics are covered. The political orientation of a publication is also to be taken into account as a possible dimension for differentiation. This results in two sub-questions:

Sub-question 1: Are there differences between newspapers of different political orientations in terms of the diversity characteristics gender, age and origin?

Depending on their political orientation, newspapers may prefer to cover particular topics or pursue a particular type of reporting (cf. Hanke 2011: n.p.; Deutschland.de 2020: n.p.). Garz et al. (2020) looked at this by analyzing Facebook data. This shows, for example, that Süddeutsche Zeitung and Die Zeit are classified as more left of center; Handelsblatt and Bild are in the center of the spectrum; and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Die Welt are right of center (cf. Garz et al. 2020: 102). The two orientations bourgeois-conservative and left-wing liberal are contrasted in the hypotheses by way of example.

›Conservatism‹ refers to a political worldview that strives to maintain traditions. Continuity and security are its most important features (cf. Schubert/Klein 2020: n.p.). Origin and homeland are also key pillars (cf. NdM-Glossar 2021: n.p.). Bourgeois-conservative newspapers also focus more on economic issues, as businesspeople and decision-makers make up a large part of their readership (cf. Hanke 2011: n.p.).

On the other side is liberalism, advocating each individual’s right to develop freely and rejecting all forms of coercion (cf. Thurich 2011a: n.p.). »Liberal« is considered a synonym for »tolerant,« »open-minded,« and »not dogmatic« (cf. Hug 2019: n.p.). When someone is politically left-wing, their focus is on social justice and equality (cf. Thurich 2011b: n.p.). Left-wing liberalism is shaped by and combines the values and attitudes of liberalism with elements of left-wing politics (cf. Hug 2019: n.p.).

For these reasons, we anticipate that left-wing liberal newspapers strive for more diversity than bourgeois-conservative ones. The hypotheses are therefore as follows:

H1a: The proportion of women is lower at bourgeois-conservative newspapers than at left-wing liberal newspapers.

H1b: The age distribution is smaller at bourgeois-conservative newspapers than at left-wing liberal newspapers.

H1c: The proportion of journalists of non-German origin is lower at bourgeois-conservative newspapers than at left-wing liberal newspapers.

Sub-question 2: Are there differences between the editorial office and leadership positions with regard to the diversity characteristics gender, age, and origin?

Leadership positions comprise (deputy) editors in chief, (deputy) heads of department, and lead editors in newspaper editorial offices. All other journalists working for the newspaper are categorized as »editorial office.«

The »Act for the Equal Participation of Men and Women in Leadership Positions in Private Enterprise and Public Service« came into effect in Germany in May 2015 (cf. Bundesgesetzblatt 2015: n.p.), as part of the Federal Equality Act. According to the federal government, there have been some changes in leadership positions at companies, but this change has been very slow and insufficient (cf. BMFSFJ 2021: n.p.). The proportion of women in German editorial office leadership positions in 2014/2015 was 33%; the figure for higher levels such as editor in chief was just 21% (cf. Lauerer et al. 2019: 88). We can therefore assume that there are still fewer women than men in journalistic leadership positions.

H2a: The proportion of women is higher in editorial offices than in leadership positions.

According to a study by CRIF Bürgel GmbH (2018: n.p.), the mean age of managers in Germany in 2018 was 51.9 years. The mean age of the working population in the same year was 44 years (cf. DESTATIS 2018: n.p.). The journalism sector is no exception here – those in leadership roles are likely to be older on average than editorial office staff. Furthermore, the age distribution is likely to be more concentrated at leadership levels, because employees with more years of professional experience are more likely to take up journalistic leadership positions. Editorial offices also include those just starting out in the profession, so a broader age distribution can be expected there than at the leadership level.

H2b: The age distribution in editorial offices is broader than in leadership positions.

People with a background of migration are generally under-represented in leadership positions (cf. Hanewinkel 2021). While those with a background of migration made up a total of 24.4% of the workforce in Germany in 2019 (cf. DESTATIS 2020: n.p.), a study by the German Centre for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM) showed that the proportion of people with a background of migration in leading positions in the media was just 16.4% (cf. DEZIM-Institut 2020: n.p.). According to a study by Neue deutsche Medienmacher:innen, just 6.4% of editors in chief in Germany have a background of migration (cf. Boytchev et al. 2020: 9). We can therefore assume that the proportion of journalists in leadership positions with a background of migration is slightly lower than in editorial offices.

H2c: The proportion of journalists of non-German origin is higher in editorial offices than in leadership positions.

Age is one of the most common dimensions in diversity research (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 7f.). Rising life expectancy and low birth rates are having an impact on the changing composition of the workforce (cf. Rahnfeld 2019: 8ff.). Up to five different generations currently work together in the same team, bringing with them their different values, attitudes and experiences. This can result in conflict. In Switzerland, for example, 27% of those surveyed stated that they had observed negative prejudice against older employees in their work teams (cf. Grote/Staffelbach 2020: 28). Other studies show that a working environment featuring age discrimination is linked to poorer performance (cf. Kunze et al. 2013: 413). It is therefore important to foster and retain the opportunities that generational diversity offers and to break down age-related stereotypes. Mentoring programs, flexible working, and mixed-age teams can all help to put generational diversity to positive use (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 7f.). This study measures the age characteristic in years (rather than generations or age groups).

When it comes to the gender dimension, the focus is on integrating all identities and genders into the company and its culture, and enabling everyone to enjoy the same opportunities. When someone feels accepted as an individual, they are better able to fulfil their potential (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 11f.). Gender-neutral processes, teams with a good gender mix, and training on leadership skills or to combat prejudices, for example, can help to prevent the phenomenon of the glass ceiling[3] and problems like wage inequality and rigid working models (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 11). Further focus topics in gender diversity include discrimination against women in everyday working life, which may include oppression, harassment, and mobbing (cf. Brügger 2021: n.p.; Salin 2015: 69ff.), and flexible working hours models for fathers who also want to spend more time with their families (cf. Monitor Familienleben 2012: 17). This paper reduces gender[4] to the two genders of women and men, because comparable investigations look at equality and equality of opportunity between women and men. Studies show that women in Germany earn around 20% less than men (cf. Fünffinger 2021: n.p.).

Origin is used here to mean the dimension of ethnic background and nationality in line with the Diversity Charter, which refers to the cultural and language resources of those in work (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 9). In a globalized economy, dealing openly and professionally with cultural diversity in the company environment is fundamental (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 9f.). Recommended measures include, for example, putting together diverse teams and providing intercultural and language training (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 10). A diversity of origin is the result of migration. Almost 16 million international migrants are estimated to live in Germany (cf. IOM 2022: 24). With a lack of sufficient data on the ethnic origin of employees in large organizations (cf. Müller 2005: 230), origin is generally recorded based on nationality and ›background of migration‹ (cf. DESTATIS 2021b: n.p.). The background of migration can be understood to different degrees; because we have not recorded it systematically, we can only assume the origin based on the person’s own statement of nationality.

Method

Both, existing public secondary data, such as the names of journalists and people in leadership roles, and new primary data was collected (cf. Becker 2021: n.p.). The primary data is the diversity characteristics age, gender, and nationality, which were collected in person in a survey.

The following newspaper editorial offices were selected for the investigation because, as newspapers of record, they are highly relevant to the public discourse (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 51f.; Pastor 2023: n.p.): Die Zeit, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), Bild, Der Spiegel, and Die Welt. These newspapers are also those with the largest print and online reach in Germany (Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 12ff.), and are intended to reflect the full spectrum of political orientations (cf. Garz et al. 2020: 98, 102). Die Zeit and Süddeutsche Zeitung were categorized as left-wing liberal; FAZ and Die Welt as bourgeois-conservative. All other editorial offices were excluded from the analysis of the political orientation in order to highlight the opposing poles.

Given that the news titles were chosen in advance, the sample does not consist of randomly selected respondents. The intention was to collect a full data set from selected editorial offices. However, the accessibility of the personal data and the response behavior of the respondents both have an impact on the sample (cf. Häder/Häder 2019: 333ff.; Stein 2019: 136). Once the newspaper editorial offices had been chosen, work began to collect the data from journalists. This was conducted in two stages in July and August 2021. The first step was to find the names of journalists in the selected editorial offices and leadership levels using the legal notice of the respective media company or newspaper. Further research was conducted on social media, such as LinkedIn and Twitter, as these are used by many journalists. In most cases, the gender of the person could be determined from the name. In addition, around a third of the sample had publicly accessible fact files that provided information on their age, origin, and gender. These fact files were found either in posts on the websites of the employers or, for example, on people’s private websites. The second step was to contact people whose data could not be fully collected in the first stage in person via email or LinkedIn, informing them of the research project and asking them their age, gender, and origin. There was great willingness and interest among the respondents, with a return rate of around 80%. The sample size is n = 1503, accounting for around 11% of newspaper journalists in Germany. The German Journalists Association [Deutscher Journalisten-Verband, DJV] estimates that around 13,500 journalists are employed at German newspapers and their online outlets (cf. Von Garmissen/Biresch 2019: 8).

The following information and categories were secured for each data point: newspaper title, orientation, role, hierarchical level, name, gender, age, nationality. The hierarchical level is divided into editorial office and leadership position. The editorial office level comprises various professions: journalists, lead editors, freelance journalists, reporters, authors, and correspondents. Editors in chief, heads of department, heads of editorial offices, chief editors, and managing editors were assigned to the leadership level. The diversity characteristic origin was operationalized using the nationality requested.

Because we were unable to collect complete data on all three characteristics for all people, we adjusted the samples for gender, age, and origin in each analysis, so that only complete data sets, and thus sub-samples, were included in the analysis in each case. The distribution of the characteristics is described based on the adjusted data (cf. Stein 2019: 126).

The hypotheses are tested using a group comparison between dependent and independent variables. To do this, the three diversity characteristics as dependent variables were tested for significance with the categories orientation and hierarchical level as independent variables in each case. This analysis serves to find factors that potentially influence the distribution of the characteristics (cf. Stein 2019: 120ff.). First, each variable of the hypotheses was subjected to a comparison of mean and standard deviations, before being tested for a significance level of 5% using a suitable test. For the variables gender and origin, a chi-squared test was used (cf. Pearson 1990). This tests whether two categorial variables are linked (cf. Universität Zürich 2021: n.p.).

If there were perfect statistical independence, the frequencies of the characteristic combinations would be as expected in theory. If the observed frequencies differ from those expected, there is a statistical correlation (cf. Diaz-Bone 2013: 82f.). The p value shows whether there is a statistically significant difference or correlation.

Furthermore, the chi-squared test was also used to test the strength of the correlation in each case. According to Lakens (2013), the strength of evidence is among the most important results of empirical studies. This was tested using Cramér’s V, a measure of association on a scale of 0 to 1 (cf. Diaz-Bone 2013: 85). V=1 would denote a very strong correlation.

A Levene’s test was used to measure the metric variable age, as the breadth of the distribution is what interests us for this characteristic. The standard deviation, rather than the mean values, are therefore what matters here. Standard deviation and variance are the most common measures of dispersion for metric variables. If the difference between the characteristics is low, these values are small (cf. Diaz-Bone 2013: 51). The Levene’s test measures whether there are different variances between the groups (cf. Walther 2020: n.p.). If p<0.05, this means that there is a statistically significant difference between the variances.

Results

In order to answer the overarching question of how diverse the staff of German newspaper editorial offices are, the distributions by gender, age, and origin will first be described and compared with population statistics. The hypotheses are assigned to the sub-questions accordingly and will be assessed based on the analysis results.

To what extent does the distribution of the characteristics gender, age, and origin among journalists in German newspaper editorial offices currently reflect diversity?

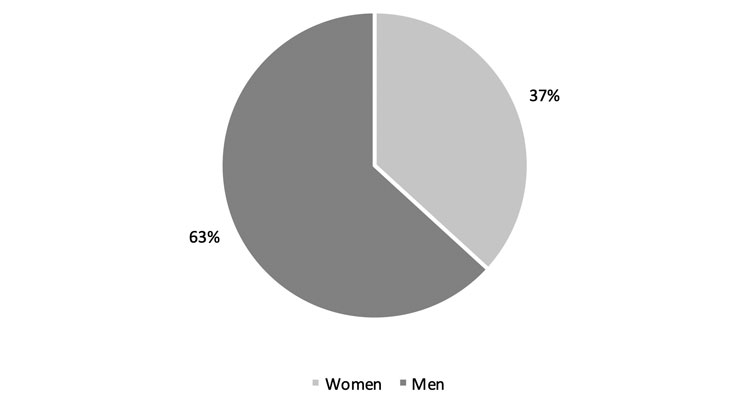

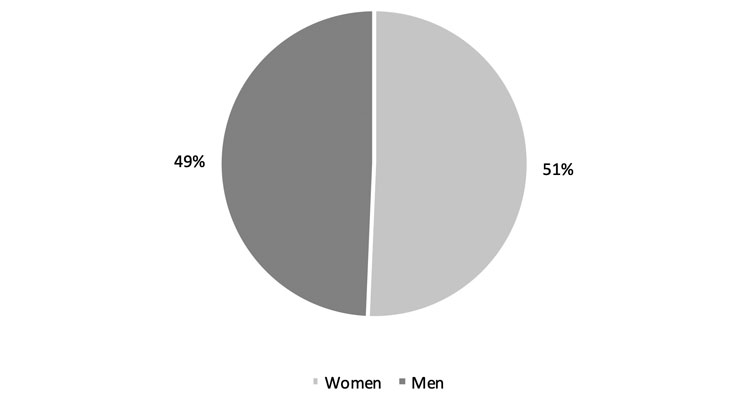

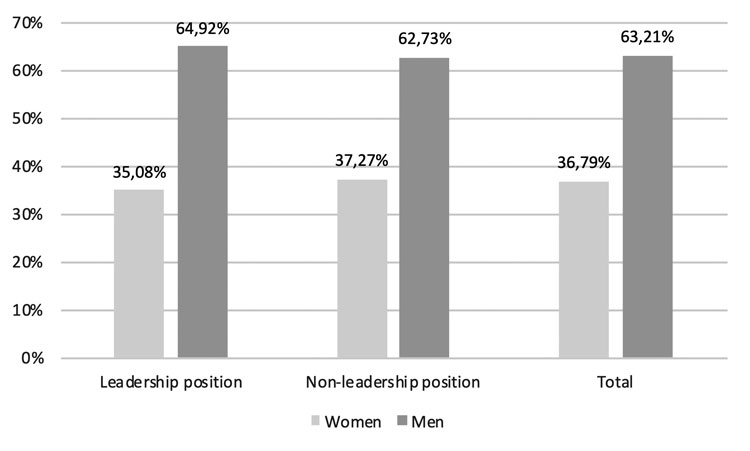

The characteristic gender comprises 1,503 data points (= n). The total sample contains 954 men (63%) and 556 women (37%) (Fig.1). Women are thus clearly under-represented, given that they make up around 51% of Germany’s population in 2021 (cf. DESTATIS 2024a: n.p.).

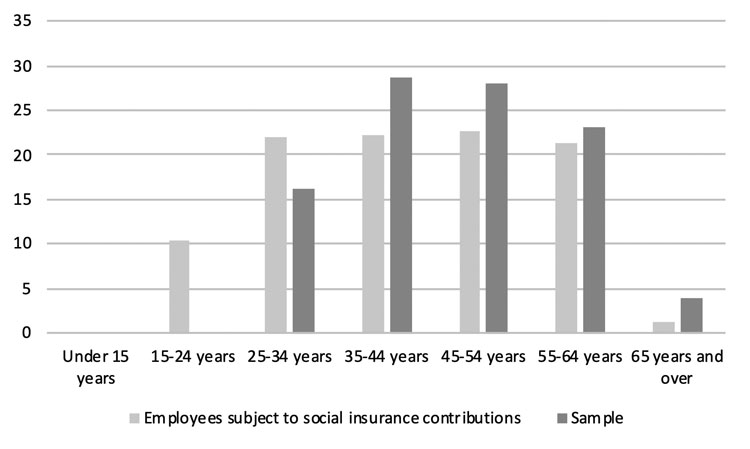

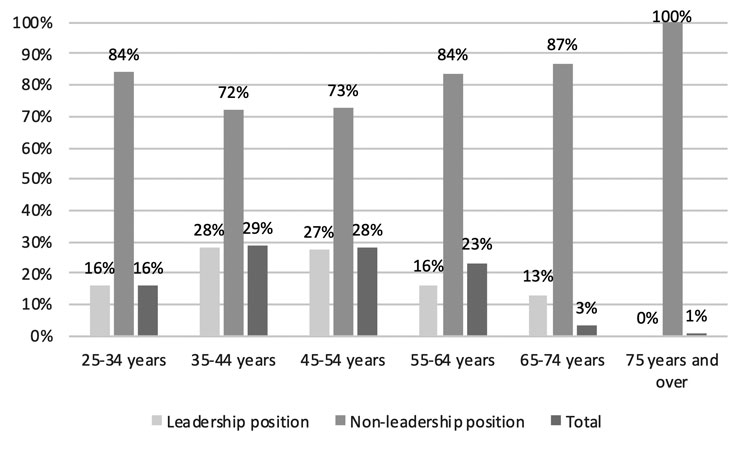

The mean age in the sample (n = 1,169) is 46.6 years, with a median of 46 years. The lowest value is 25 years and the highest value 91 years. The age range is therefore relatively large, starting relatively high and exceeding retirement age. Figure 2 shows the difference between this and the distribution of employees subject to social insurance contributions in 2021. The difference is also reflected in the mean, which is almost three years higher than that of the working population (cf. Methodik; DESTATIS 2018: n.p.).

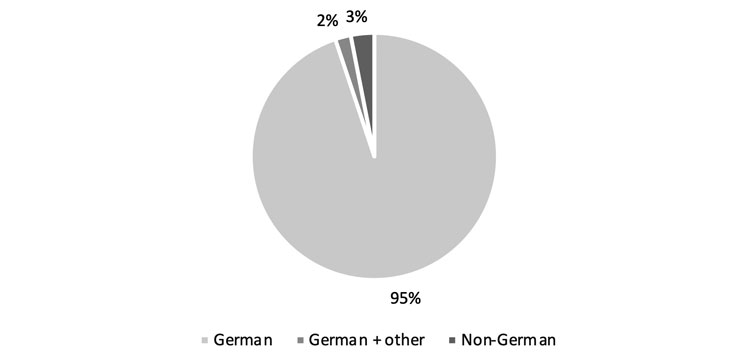

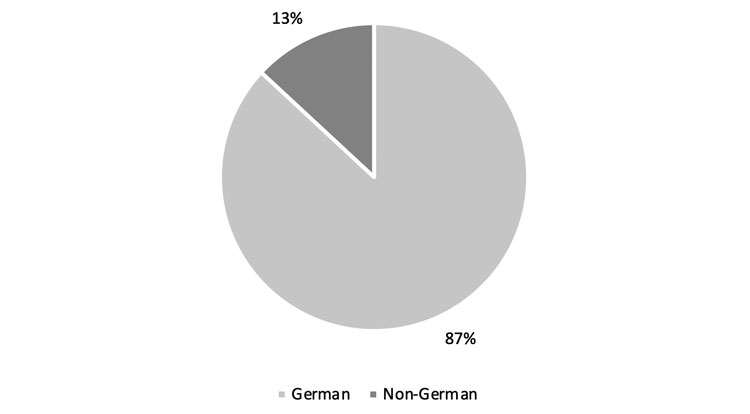

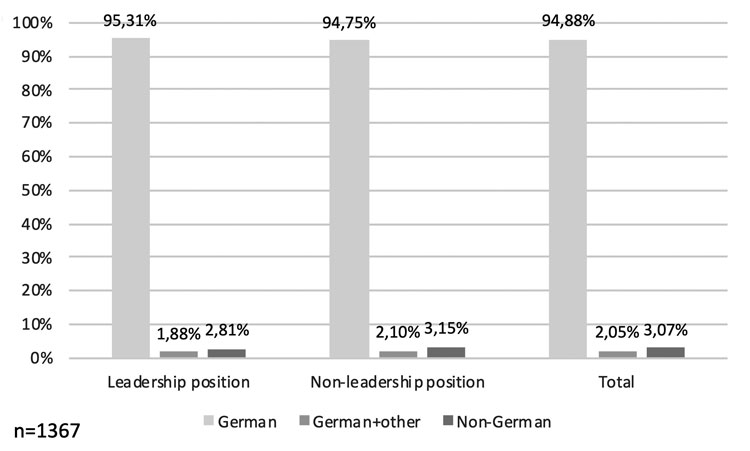

The analysis of the origin (n = 1367) shows a disproportionate proportion of people of German nationality and/or origin. While the proportion of people of non-German nationality in Germany in 2021 is around 13% (cf. DESTATIS 2022: n.p.:), the figure in our sample is just 3% (Fig. 3). This result is approximately the same as those of previous studies that estimated the proportion of journalists with a background of migration in Germany at 5 to 10 % (cf. Boytchev et al. 2020).

Fig. 1.1

Gender distribution in the sample (2021)

Illustration by the authors

Fig. 1.2

Gender distribution in society (2021)

Source: DESTATIS 2024a: o.S; illustration by the authors

Fig. 2

Age distribution in the sample compared to all employees subject to social insurance contributions in 2021

Source: DESTATIS 2024b: n.p.

In order to assess the hypotheses, the data was subjected to a chi-squared test [χ²] (age, origin) or a Levene’s test (age).

Are there differences between newspapers of different political orientations with regard to the diversity characteristics gender, age, and origin?

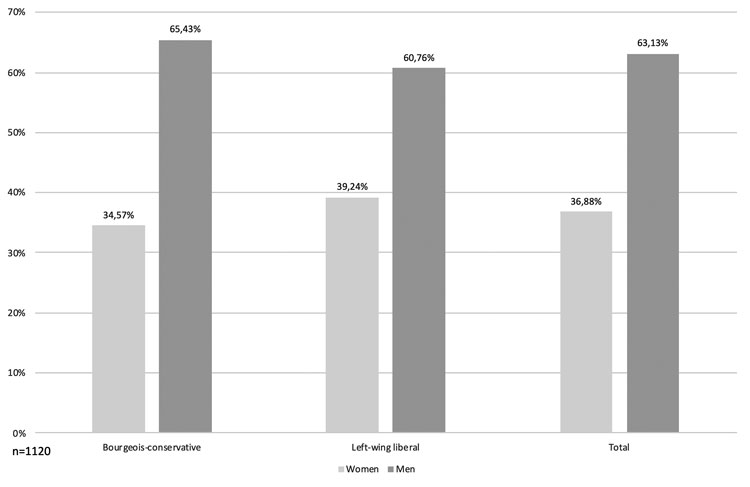

Only the editorial offices of contrasting political orientations were investigated for this analysis. Freelance authors were excluded from the sample, as they may work for multiple newspapers. The sample size was thus reduced to n = 1120.

H1a supposes a lower proportion of women at bourgeois-conservative newspapers than at left-wing liberal papers. Although there is indeed a slightly lower proportion of women at bourgeois-conservative newspapers, the difference is not statistically significant (Fig. 4).

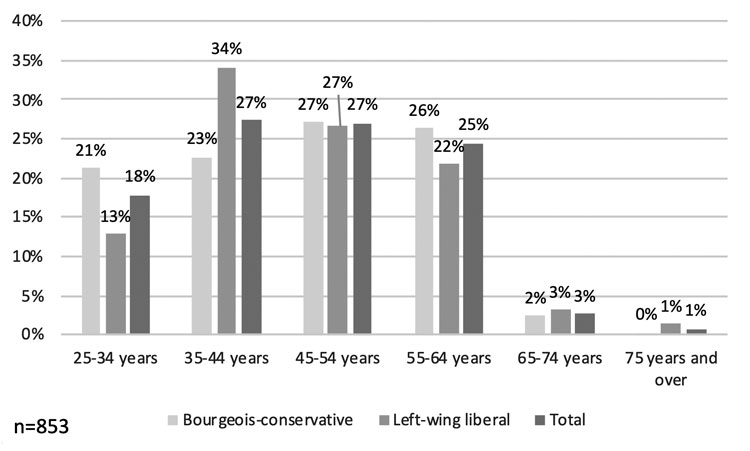

H1b supposes that the age distribution at left-wing liberal newspapers will be larger than that at bourgeois-conservative papers. No significant differences could be measured here, either. The hypothesis must therefore be rejected (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.1

Distribution of the sample by nationality (self-declaration by respondent)

Source: Authors’ own

Fig. 3.2

Distribution of nationalities in the population of Germany in 2021

Source: DESTATIS 2024a: n.p.

Fig. 4

Gender distribution in the editorial offices of contrasting political orientations

Source: Authors’ own

Fig. 5

Age distribution in the editorial offices of contrasting political orientations

Source: Authors’ own

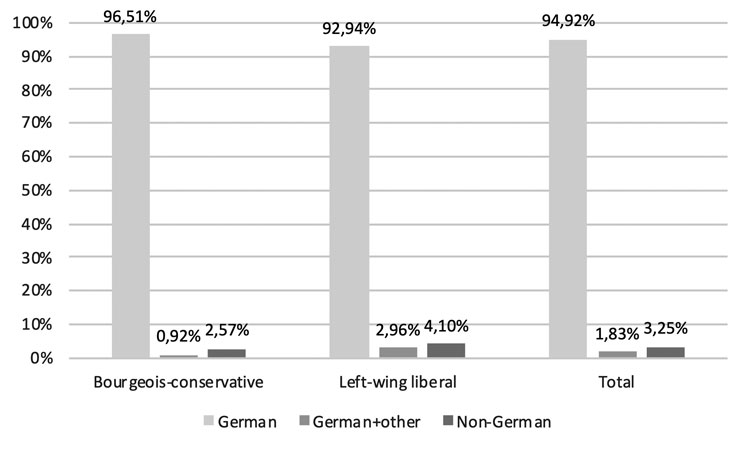

H1c supposes a lower proportion of people of non-German origin at bourgeois-conservative newspapers. Figure 6 shows the difference. The analysis also shows that there is a significant difference between bourgeois-conservative and left-wing liberal newspapers with regard to the proportion of non-German journalists.

Fig. 6

Nationality (self-declaration) in the editorial offices of newspapers with contrasting political orientations

Source: Authors’ own

Are there differences between the editorial office and leadership position levels with regard to the diversity characteristics gender, age, and origin?

Hypothesis H2a supposes a higher proportion of women in the editorial offices of the newspapers than at the leadership level. Figure 7 shows that the proportion is around 37% in editorial offices and around 35% at leadership level. According to the significance test, however, this difference is not significant. The p value is around 0.47.

H2b supposes a broader age distribution in the editorial office than at the leadership level. Figure 8 shows that the age range is indeed wider in non-leadership positions. The Levene’s test gives a value of p < 0.05 here, meaning that the difference is significant. H2b can therefore be confirmed.

Hypothesis H2c predicts that there is a higher proportion of people of non-German origin in the editorial offices than at a leadership level. There is indeed a difference in the absolute figures (see Fig. 9). However, just as for H2a, the difference is not significant, but corresponds to the extremely low proportion of people of non-German origin in the total sample.

Fig. 7

Proportion of women and men in the sample by hierarchical level

Source: Authors’ own

Fig. 8

Frequency distribution of the sample by age group and hierarchical level

Source: Authors’ own

Fig. 9

Nationality of the sample and leadership position

Source: Authors’ own

The data analysis proves that there is a correlation between a newspaper’s political orientation and the proportion of staff of non-German origin, but not between the orientation and the gender distribution or age range. According to the results, left-wing liberal newspapers have staff with a more diverse range of origins than bourgeois-conservative papers. In addition, the hierarchical level has a significant influence on the age range, but not on the diversity characteristics gender and origin. Editorial offices were found to be more diverse in terms of age than leadership positions. Hypotheses H1c and H2b are confirmed. Hypotheses H1a, H1b, H2a, and H2c must be rejected.

Table 1

Results of the analysis of hypotheses H1

| Political orientation | Left-wing liberal | Bourgeois-conservative | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a) Gender | Proportion of women 39.24% | Proportion of women 34.57% | χ²= 2.626a p=0.105 |

| H1b) Age | Mean=47 years (SD=10.91) | Mean=46,28 years (SD=11.39) | p=0.077 |

| H1c) Origin | Proportion of German+other & non-German 7.06% | Proportion of German+other & non-German 3.49% | χ²=7.633a p=0.022* |

Answer: There are no significant differences in the gender and age distribution in the newspaper editorial offices of contrasting political orientations; however, there is more diversity of origin at left-wing liberal editorial offices.

Table 2

Results of the analysis of hypotheses

| Hierarchical level | Editorial office | Leadership position | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2a) Gender | Proportion of women 37.27% | Proportion of women 35.08% | χ²= 0.5256a p=0.469 |

| H2b) Age | Mean=46.91 years (SD=11.55) | Mean=45,61 years (SD=9.01) | p<0.001** |

| H2c) Origin | Proportion of German+other & non-German 5.32% | Proportion of German+other & non-German 5.08% | χ²=0.026 a p=0.987 |

Answer: There are no significant differences in the gender distribution and origin between editorial offices and the leadership level; however, the age range in editorial offices is broader than at leadership level.

Discussion and conclusion

The results show that women are under-represented in newspaper journalism: Just 36.8% of the journalists in the sample are women. In fact, the proportion of women journalists actually fell slightly compared to the results of the study by Hanitzsch et al. (2019) from 2014/2015. The proportion of women then was 40%, although it is important to note that the samples in 2014/2015 were significantly smaller than in this study, with 775 German journalists surveyed (cf. Steindl et al. 2019: 45). Neither the political orientation of the newspaper nor the hierarchical level has a statistically relevant influence on this discrepancy.

From this investigation, we can thus conclude that, despite measures such as Germany’s statutory quota of women, there is still an unequal gender distribution in newspaper journalism. As a general rule, many years of professional experience are needed in order to advance to a leadership position. On average, women journalists have around six years less professional experience than their men colleagues (cf. Dietrich-Gsenger/Seethaler 2019: 59). This could be one reason for the gender inequality at leadership levels.

The mean age of the total sample is 46.6 years (median: 46 years). The working population in Germany in 2017 was 44 years old on average (cf. DESTATIS 2018: n. p.). Furthermore, the youngest person in the sample was 25 years old and the oldest 91 years old; the youngest age group, 15-24-year-olds, is not represented at all. This may be in part due to the strong increase in academic qualifications required in the profession in recent years. According to Dietrich-Gsenger and Seethaler (2019: 60), even in 2015, around three quarters of German journalists had an academic degree. The comparison with all employees subject to social insurance contributions also clearly shows that newspaper journalists are relatively old – no-one is under 25 years old, and the over-65 age group is significantly over-represented. There is no significant difference between left-wing liberal and bourgeois-conservative newspapers in this regard. The age distribution in editorial offices is significantly broader than at leadership level. This can be explained by the fact that both those starting out in the profession and employees with many years of experience work in the editorial office. Leadership positions, on the other hand, are usually held by people who already have a certain amount of professional experience. This is also clear from the mean age of people in leadership roles in Germany, which was 51.9 years in 2018 (cf. CRIF Bürgel GmbH 2018: n.p.).

The investigation showed that journalists with a history of migration are still under-represented in newspaper editorial offices. Of the 1,367 respondents in the sample, just 42 stated that they were of non-German heritage and 28 that they had an additional nationality – a total percentage of 5.1%. The 3% of journalists of non-German nationality contrast with the figure of 13% for the population as a whole (cf. DESTATIS 2022: n.p.). The political orientation of the newspaper is significantly related to the nationality of the journalists. At left-wing liberal newspapers, the proportion of journalists of non-German or dual nationality is around 7%; the figure at bourgeois-conservative newspapers is just 3.5%. This could be due to the more open-minded, tolerant attitude of left-wing liberalism and its efforts to achieve social equality (cf. Hug 2019: n.p.). This investigation found no significant correlation between hierarchical level and origin. People of non-German origin are under-represented in the sample as a whole and thus also at leadership level.

A core challenge for the empirical investigation of diversity in newspaper editorial offices is the access to personal data. As a result, the data sets for the individual newspapers are neither complete nor of equal size. The number of data sets depended on the digital presence on the respective website and social media, and on the respondents’ participation. We can assume that not all journalists who write for the newspapers investigated have agreed to be named on the company website. Journalists who were newly employed during the data collection period presumably are not yet listed on the website either. Additional research on LinkedIn and Twitter could only compensate for this deficit to a limited extent, as not all journalists have a profile there. However, the return rate of 80% among the journalists contacted in person indicates that the target group is very willing to support research in this field.

We were only able to investigate a selection of newspapers and diversity dimensions. Sexual orientation, social background, and level of education are all examples of further aspects that could be important in an investigation of diversity in journalism. Gender identities beyond simply men and women were also excluded in this case. The nationality alone is not sufficient to draw conclusions on ethnic origin. Extensive collection of primary data could improve the quality of the results, but also runs the risk of distorting the picture through lower return rates and people’s tendency to give responses they believe to be socially desirable.

When it comes to the results on the political orientation of newspapers, it is important to remember that, because small sub-samples were used, our results cannot be used to draw overall conclusions. Furthermore, the political orientation of a newspaper is often an external classification. Investigating based on the political orientation can therefore only ever be an attempt to uncover factors that could potentially influence diversity in journalism, and cannot be used as a decisive criterion. Incorporating journalists working for regional publications in the analysis would also be useful.

All in all, this paper reflects a sample of the totality of journalists in German newspaper editorial offices and their leadership positions. The results allow initial insights into the diversity of journalism. Further research could look at the social background, political attitude, and worldview of journalists. In addition, it could consider different career paths for journalists, such as journalists with academic degrees and others with traditional vocational training. Other newspaper titles could also be investigated. More detailed analysis by topic areas or departments would also be useful in order to provide comparisons within the editorial offices. Comparisons of the diversity in editorial offices with that in television, radio, and online journalism would also be interesting. Another role of further research would be to find out the reasons why people with a background of migration are under-represented in newspaper editorial offices – clarifying whether this is due to the language requirements, a lack of permeability in the education system, a lack of networking and cultural capital, or discrimination in the broadest sense (cf. Oulios 2009: 140-143).

It falls to journalism to develop the necessary strategies. Despite progressive developments in recent years, there is still insufficient diversity among newspaper journalists in Germany in terms of gender, age, and origin. This study highlights the need for action.

About the authors

Roxane Biller, M.A. (*1995) has been a research associate in the Digital and Media Management department at Hamburg Media School since 2022. Before this, she completed a master’s degree in Multilinguality and Education at the University of Hamburg. Contact: r.biller@hamburgmediaschool.com

Seraina Cadonau, MBA (*1992) completed her MBA in Digital and Media Management at Hamburg Media School in 2021.

Marion Frank, MBA (*1993) has worked in software and product development since 2022. Her focus is on establishing diverse teams in order to make this specialist field more attractive to under-represented groups and to promote equality of opportunity. She completed her MBA in Digital and Media Management at Hamburg Media School in 2021.

Translation: Sophie Costella

References

Becker, Florian (2021): Primärdaten, Sekundärdaten und Meta-Analyse als Datenquelle in der Marktforschung. In: Wirtschaftspsychologische Gesellschaft. https://wpgs.de/fachtexte/forschungsprozess/6-primaerdaten-sekundaerdaten-und-meta-analyse-als-datenquelle-in-der-marktforschung/ (7 September 2021).

BMFSFJ, Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2021): Quote für mehr Frauen in Führungspositionen: Privatwirtschaft. https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/themen/gleichstellung/frauen-und-arbeitswelt/quote-privatwitschaft/quote-fuer-mehr-frauen-in-fuehrungspositionen-privatwirtschaft-78562 (14 August 2021).

Boytchev, Hristio; Horz, Christine; Neumüller, Malin; Oulios, Miltiadis; Vassiliou-Enz, Konstantina (2020): Viel Wille, kein Weg. Diversity im deutschen Journalismus. In: Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen. https://neuemedienmacher.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200509_MdM_Bericht_Diversity_im_Journalismus.pdf (1 September 2021).

Brügger, Nadine (2021): »Da schreit ein Kind, hab ich das mit dir gezeugt?« – Tamedia-Journalistinnen prangern strukturellen Sexismus an. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/da-schreit-ein-kind-hab-ich-das-mit-dirgezeugt-tamedia-journalistinnen-prangern-strukturellen-sexismus-anld.1605472?reduced=true (2 September 2021).

Bundesgesetzblatt (2015): Gesetz für die gleichberechtigte Teilhabe von Frauen und Männern an Führungspositionen in der Privatwirtschaft und im öffentlichen Dienst. Bundesanzeiger Verlag: Bundesgesetzblatt (bgbl.de) (9 September 2021).

Charta der Vielfalt (2021a): Factbook Diversity. Positionen, Zahlen, Argumente. https://www.charta-der-vielfalt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Diversity-Tag/2021/Factbook_2021.pdf (26 July 2023).

Charta der Vielfalt (2021b): Die Initiative Charta der Vielfalt. https://www.chartader-vielfalt.de/ueber-uns/ueber-die-initiative/ (17 September 2021).

Charta der Vielfalt (2023): Charta der Vielfalt – Für Diversity in der Arbeitswelt. https://www.charta-der-vielfalt.de/ (15 August 2023).

CRIF Bürgel GmbH (2018): Durchschnittsalter von Führungskräften in Deutschland nach Bundesländern im Jahr 2018. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/182536/umfrage/durchschnittsalter-von-geschaeftsfuehrern-nach-bundeslaendern-und-geschlecht/ (20 August 2021).

Deutschland.de (2020): Überregionale Zeitungen in Deutschland. https://www.deutschland.de/de/topic/wissen/ueberregionale-zeitungen (1 September 2021).

DEZIM-Institut, Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (2020): Verteilung der Führungskräfte in Deutschland mit Migrationshintergrund in verschiedenen Gesellschaftsbereichen* im Jahr 2018/19. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1182686/umfrage/fuehrungskraeftemit-migrationshintergrund-und-bereich/ (20 August 2021).

Diaz-Bone, Rainer (2013): Statistik für Soziologen (2. ed.). Konstanz, Munich: UVK.

Dietrich-Gsenger, Marlene; Seethaler, Josef (2019): Soziodemografische Merkmale. In: Hanitzsch, Thomas; Seethaler, Josef; Wyss, Vinzenz (Hrsg.): Journalismus in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 51-70.

Fünffinger, Anita (2021): »Eklatante Ungerechtigkeit« – seit Jahren. Equal Pay Day. In: tagesschau.de. https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/equal-pay-day-105.html (11 July 2021).

Gardenswartz, Lee; Rowe, Anita (1994): Diversity Teams at Work. Capitalizing on the power of diversity. Chicago: Irwin Professional Pub.

Garz, Marcel; Sörensen, Jil; Stone, Daniel (2020): Partisan selective engagement: Evidence from Facebook. In: Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 177, pp. 91–108.

Grote, Gudela; Staffelbach, Bruno (2020): Schweizer HR-Barometer 2020. Digitalisierung und Generationen. Universitäten Luzern, Zürich und ETH Zürich. https://www.unilu.ch/fileadmin/fakultaeten/wf/institute/hrm/dok/HR-Barometer/2020/HRBarometer2020_Final.pdf (4 August 2021).

Häder, Michael; Häder, Sabine (2019): Stichprobenziehung in der quantitativen Sozialforschung. In: Baur, Nina; Blasius, Jörg (eds.): Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 333-348.

Hanappi-Egger, Edeltraud (2012): Diversitätsmanagement und CSR. In: Schneider, Andreas; Schmidpeter, René (eds.): Corporate Social Responsibility. Verantwortungsvolle Unternehmensführung in Theorie und Praxis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Gabler, pp. 177-190.

Hanewinkel, Vera (2021): Fortschritte: ja, gleichberechtigte Teilhabe: nein – zum Stand der Integration. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (ed.). https://www.bpb.de/themen/migration-integration/regionalprofile/deutschland/344051/fortschritte-ja-gleichberechtigte-teilhabe-nein-zum-stand-der-integration/ (5 February 2025).

Hanitzsch, Thomas; Lauerer, Corinna (2019): Berufliches Rollenverständnis. In: Hanitzsch, Thomas; Seethaler, Josef; Wyss, Vinzenz (eds.): Journalismus in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 135-163.

Hanitzsch, Thomas; Seethaler, Josef; Wyss, Vinzenz (2019): Zur Einleitung: Journalismus in Schwierigen Zeiten. In: Hanitzsch, Thomas; Seethaler, Josef; Wyss, Vinzenz (eds.): Journalismus in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 1-24.

Hanke, Katja (2011): Die Tageszeitungen Deutschlands. https://web.archive.org/web/20160209140508/http:/www.goethe.de/ins/cl/de/sao/kul/mag/med/8418130.html (1 September 2021).

Harrison, David A.; Sin, Hock-Peng (2006): What is diversity and how should it be measured? In: Konrad, Alison M.; Prasad, Pushkala; Pringle, Judith K. (eds.): Handbook of workplace diversity. London: Sage Publications, pp. 191–216.

Hasebrink, Uwe (2016): Meinungsbildung und Kontrolle der Medien. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/medien-und-sport/medienpolitik/172240/meinungsbildung-und-kontrolle-der-medien (14 July 2021).

Hasebrink, Uwe; Hölig, Sascha; Wunderlich, Leonie (2021): #UseTheNews. Studie zur Nachrichtenkompetenz Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in der digitalen Medienwelt. Hamburg: Verlag Hans-Bredow-Institut. https://doi.org/10.21241/ssoar.72822 (17 September 2021).

Hug, Heiner (2019): Linksliberal und rechtskonservativ. In: Journal21. https://www.journal21.ch/linksliberal-und-rechtskonservativ (30 August 2021).

Käppner, Joachim; Mayer, Christian (2020): Die Lebensbegleiterin. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/medien/geschichte-sueddeutsche-zeitung-sz-75-jahre-1.4998980 (9 September 2021).

Kleinsteuber, Hans-Jürgen (2005): Mediensysteme. In: Weischenberg, Siegfried; Kleinsteuber, Hans-Jürgen; Pörksen, Bernhard (eds.): Handbuch Journalismus und Medien. Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, pp. 275-280.

Kunze, Florian; Boehm, Stephan; Bruch, Heike (2013): Organizational performance consequences of age diversity: Inspecting the role of diversity-friendly HR policies and top managers’ negative age stereotypes. In: Journal of Management Studies, 50(3), pp. 413–442.

Lakens, Daniel (2013): Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. In: Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 4, p. 863.

Lünenborg, Margreth; Fritsche, Katharina; Bach, Annika (2011): Migrantinnen in den Medien. Darstellungen in der Presse und ihre Rezeption. Bielefeld: transcript.

Mensi-Klarbach, Heike; Hanappi-Egger, Edeltraud (2018): Diversitätsmanagement 2.0. Die individuellen Bedürfnisse rücken in den Fokus. In: Zeitschrift Führung + Organisation, 87(4), pp. 220-224.

Monitor Familienleben (2012): Einstellungen und Lebensverhältnisse von Familien. Ergebnisse einer Repräsentativbefragung im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Familie. Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach. https://www.ifd-allensbach.de/fileadmin/studien/Monitor_Familienleben_2012.pdf (10 August 2021).

Müller, Daniel (2005): Ethnische Minderheiten in der Medienproduktion. In: Geißler, Rainer; Pöttker, Horst (eds.): Massenmedien und die Integration ethnischer Minderheiten in Deutschland. Problemaufriss – Forschungsstand – Bibliographie. Bielefeld: transcript, pp. 223-237.

NdM-Glossar (2021): Bürgerlich (konservativ). Glossar. In: Neue Deutsche Medienmacher. https://glossar.neuemedienmacher.de/glossar/buergerlich-konservativ/ (30 August 2021).

Neuberger, Christoph; Kapern, Peter (2013): Grundlagen des Journalismus. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Niggemeier, Stefan (2018): Journalisten mit Migrationshintergrund. »Ich habe mich selten türkischer gefühlt als in den vergangenen Tagen«. In: Übermedien. https://uebermedien.de/30092/ich-habe-mich-selten-tuerkischer-gefuehlt-als-inden-vergangenen-tagen/ (17 September 2021).

Oulios, Miltiadis (2009): Weshalb gibt es so wenig Journalisten mit Einwanderungshintergrund in deutschen Massenmedien? Eine explorative Studie. In: Geißler, Rainer; Pöttker, Horst (Hrsg.): Massenmedien und die Integration ethnischer Minderheiten in Deutschland. Vol. 2. Forschungsbefunde. Bielefeld: transcript, pp. 119-144.

Pastor, Robert (2023): Die 10 größten deutschen Leitmedien. https://pressemeier.de/2023/01/23/die-10-groessten-deutschen-leitmedien/ (4 June 24).

Pearson, Karl (1900): X. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. In: The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 50(302), pp. 157-175.

Rahnfeld, Claudia (2019): Diversity-Management. Zur sozialen Verantwortung von Unternehmen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Salin, Denise (2015): Risk factors of workplace bullying for men and women: The role of the psychosocial and physical work environment. In: Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(1), pp. 69–77.

Schubert, Klaus; Klein, Martina (2020): Konservatismus. Das Politiklexikon. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/nachschlagen/lexika/politiklexikon/17742/konservatismus (20 August 2021).

Spiller, Christian (2018): So viel mehr als ein Rücktritt. In: ZEIT ONLINE. https://www.zeit.de/sport/2018-07/mesut-oezil-fussball-rassismus-kommentarruecktritt (17 September 2021).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (2018): Erwerbstätige im Durchschnitt 44 Jahre alt – Pressemitteilung Nr. 448 vom 19. November 2018. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2018/11/PD18_448_122.html#:~:text=Erwerbst%C3%A4tige%20im%20Durchschnitt%2044%20Jahre%20alt%20%2D%20Statistisches%20Bundesamt (13 August 2024).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (2020): Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund und Beteiligung am Erwerbsleben. Migration und Integration. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Tabellen/migrationshintergrund-staatsangehoerigkeit-staaten.html (2 September 2021).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (2021a): Migration und Integration. Bevölkerung. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/_inhalt.html (10 August 2021).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (2021b): Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Tabellen/migrationshintergrund-geschlecht-insgesamt.html (10 August 2021).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (2022): Gut jede vierte Person in Deutschland hatte 2021 einen Migrationshintergrund. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2022/04/PD22_162_125.html (13 August 2024).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (2024a): Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht 1970 bis 2023 in Deutschland. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/deutsche-nichtdeutsche-bevoelkerung-nach-geschlecht-deutschland.html (23 August 2024).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (2024b): Sozialversicherungspflichtig Beschäftigte am Arbeitsort: Deutschland, Stichtag, Geschlecht, Altersgruppen. https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/e?operation=abruftabelleBearbeiten&levelindex=2&levelid=1724849205045&auswahloperation=abruftabelleAuspraegungAuswaehlen&auswahlverzeichnis=ordnungsstruktur&auswahlziel=werteabruf&code=13111-0001&auswahltext=&werteabruf=Werteabruf#abreadcrumb (28.8.2024).

Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS] (n.d.): Migration und Integration. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/_inhalt.html (23 August 2024).

Stein, Petra (2019): Forschungsdesigns für die quantitative Sozialforschung. In: Baur, Nina; Blasius, Jörg (eds.): Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 125-142.

Steindl, Nina; Laurer, Corinna; Hanitzsch, Thomas (2019): Die methodische Anlage der Studie. In: Hanitzsch, Thomas; Seethaler, Josef; Wyss, Vinzenz (eds.): Journalismus in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 25-50.

Thurich, Eckart (2011a): Liberal/Liberalismus. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/nachschlagen/lexika/pocket-politik/16483/liberal-liberalismus (30 August 2021).

Thurich, Eckart (2011b): Rechts-Links-Schema. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/nachschlagen/lexika/pocket-politik/16547/rechtslinks-schema (30 August 2021).

Universität Zürich (2021): Pearson Chi-Quadrat-Test (Kontingenzanalyse). Methodenberatung. https://www.methodenberatung.uzh.ch/de/datenanalyse_spss/zusammenhaenge/pearsonzush.html (2 September 2021).

Von Garmissen, Anna; Biresch, Hanna (2019): Welchen Anteil haben Frauen an der publizistischen Macht in Deutschland? https://www.pro-quote.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ProQuote-Studie_print_online_digital-2019.pdf (31 January 2025).

Walther, Björn (2020): Levene-Test in SPSS durchführen. ANOVA, Levene-Test, SPSS. https://bjoernwalther.com/levene-test-in-spss-durchfuehren/ (10.9.2021).

Weischenberg, Siegfried; Malik, Maja; Scholl, Armin (2006): Die Souffleure der Mediengesellschaft. Konstanz: UVK.

Wellbrock, Christian-Mathias; Klein, Konstantin (2014): Journalistische Qualität – eine empirische Untersuchung des Konstrukts mithilfe der Concept Map Methode. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

International Organization for Migration [IOM] (2022): World Migration Report. Accessible at: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022 (27 July 2023).

Zanoni, Patrizia; Janssens, Maddy (2003): Deconstructing Difference: The Rhetoric of Human Resource Managers’ Diversity Discourses. In: Organization Studies, 25(1), pp. 55–74.

Footnotes

3 This refers to the invisible barrier that results in qualified women being less likely to rise into higher leadership positions. Conversely, men should be given equal access to more flexible, family-friendly working models (cf. Charta der Vielfalt 2021a: 11).

4 The German word Geschlecht can refer both to biological sex and to social gender. The authors are aware that, in reality, this is not a dichotomous variable but a continuum. Given the data available, however, it is only possible to record two genders.

About this article

Copyright

This article is distributed under Creative Commons Atrribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and redistribute the material in any medium or format. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. You must however give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. More Information under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en.

Citation

Roxane Biller; Seraina Cadonau; Marion Frank: Diversity in journalism. An empirical analysis of gender, age, and origin in German newspaper journalism. In: Journalism Research, Vol. 8 (1), 2025, pp. 45-70. DOI: 10.1453/2569-152X-12025-14998-en

ISSN

2569-152X

DOI

https://doi.org/10.1453/2569-152X-12025-14998-en

First published online

April 2025