By Jasmin Koch, Sabine Schiffer, Fabian Schöpp and Ronja Tabrizi

Abstract: The crisis in public service media indicates various causes and areas in which structural reform is needed. Discussion is also needed on the dysfunctionality of the supervisory bodies. In this context, it is important to consider the composition of the broadcasting councils of the ARD broadcasters, the ZDF Television Council, and Deutschlandradio’s Radio Council. Since the people of Germany fund the fulfilment of the ›programming mandate‹ – as the State Media Treaties put it – through their license fee, they need to be represented in the supervisory bodies in all their diversity in order to guarantee a full range of perspectives. Quite apart from the lack of transparency regarding the way the organizations involved appoint members to the councils, it is notable that some groups and sectors of people are disproportionately represented, while others are not represented at all. In a teaching and research project, the authors used demographic data for Germany as a whole to analyze the composition of all supervisory bodies of ARD and ZDF. Part of the background to this work is the fact that the National Integration Plan also applies in this field, and there are gaps in the representation of more than a few groups of people.

Introduction

The scandal surrounding the Director of Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (rbb), Patricia Schlesinger, has pushed the topic of public service broadcasting high up the news agenda. Alongside the general disgust at the combination of personal enrichment on the one hand and ruinous cuts to programming on the other, it also became clear that many people are unaware of the history of the German media system. The particular role of the public service media (PSM) is often misunderstood. The idea behind their foundation was shaped by the experience with state broadcasters and propaganda during the Second World War, which led the Allies, in persona Hugh Greene, to found corporations modelled on the BBC.

Many people are not happy with the choice of programming and (claim that they) do not use the services – after all, many people forget the many radio stations, news apps and streaming services –, resulting in frequent calls for the PSM to be abolished and media services privatized. The license fee in particular, which is intended to guarantee the independence of the PSM, is a bone of contention for many. This is especially true when people fail to look at the media system as a whole. Many, for example, are unaware of the dimensions the change in the system of funding for broadcasting in France took on. There, the license fee was abolished and replaced by a tax-funded model, which now allows the government to allocate funds to broadcasters. The principle of self-management for PSM has therefore effectively been abolished.[1]

In Germany, rulings on broadcasting handed down by the Federal Constitutional Court have shown that the PSM do not always fulfil their programming mandate and that the limits on state interference set out in the Media State Treaties are not always adhered to (cf. Grassmuck, undated). As well as other structural weaknesses that offer potential for improvement – for example the Intendantengesetz [Director Act], the unequal rights of co-determination of employed and (regular) freelancers, the determination of funding requirements by the Kommission zur Überprüfung und Ermittlung des Finanzbedarfs der Rundfunkanstalten [Commission for Examining and Determining the Funding Requirements of Broadcasters, KEF]‚ which examines the use of the funds in random samples at best, the richly stocked and tax-guaranteed pension fund that eats up funds for programming, the dismantling of technical standards etc. –, there is also regular criticism of the supervisory bodies: the Administrative Council, but especially the broadcasting councils and Television Council, who receive complaints about programming. Both the ARD broadcasting councils and the ZDF Television Council are accused of being too close to the directorships, being insufficiently transparent about how they do or do not work, and generally failing to fulfill their role; which does not mean that specific members are not dedicated. The Radio Council of Deutschlandradio is not the subject of such frequent scrutiny, just as the many radio services are often seen less as part of the PSM. The analysis in this piece also omits the Radio Council for reasons of space.

There have been frequent calls for a more wholesale reform of the PSM, not always for benevolent reasons. The European (EU) Constitution, for example, forces everything into a neoliberal market logic which, for example, obligates the PSM to erase content from their websites. This depublication of content funded by license payers is considered »market conformity« in competition with private media providers (cf. Arena et al., 2016). Some of the current criticism of rbb in particular and the PSM in general is based on publishing houses’ well-known interest in weakening competition from the PSM. This, too, is in line with the logic of the »media as a market,« as has been seen at EU level since the implementation of the EU Reform Treaty in 2007. Given the media crisis being suffered as a result of digitalization, however, it would undoubtedly be worth considering whether public service funding systems should be expanded in order to safeguard independent research. With its dual broadcasting system, Germany is not in a bad position compared with other media systems internationally, yet, as a »pearl with defects,« the PSM need sustainable reform to secure their survival, their ability to work independently, and their credibility (cf. Schiffer 2015: 169; cf. Hallin/Mancini 2004).

It is not uncommon for constructive reform proposals to come from academia, including the »10 hypotheses for public service broadcasting« (zukunft-öffentlich-rechtliche.de), the Initiative Publikumsrat [Audience Council Initiative] (publikumsrat.de), and Unsere Medien [Our Media] (unsere-medien.de), the latter having been set up by people with professional experience in the media field. Employees, too, are organized in staff councils, freelancer lobbies and creative associations and make public comment on the current crisis – the catalog of demands from the Freienvertretung des rbb [rbb freelancer lobby] is just one example (cf. Freienvertretung des rbb 2022). Policymakers – ultimately those who decide on structural reform – have come up with contradictory proposals, as seen in the Green reform paper of October 20, 2022 (cf. Klein-Schmeink/von Notz/Grundl/Rößner 2022) and the statements on media policy made by Rainer Robra, Minister for Culture in Saxony-Anhalt (cf. Robra, undated). The audience is mainly interested in the programs on offer, and focuses its critique and suggestions there – such as in the listeners’ debate »What do you expect from public service broadcasting?« on Deutschlandfunk (cf. Baetz/Stopp 2022).

When somebody wants to complain about the programming or a specific program, they need to submit a program complaint to the responsible body. However, at ARD at least, it is not always easy to see which body that is (cf. Schiffer 2021: 234f.), and certainly not without prior knowledge. Furthermore, the complaints process often takes an extremely long time and ends with unsatisfactory answers. There is a need for reform here, too.

This teaching and research project aimed to take a closer look at the supervisory bodies for the TV services of the PSM (ARD broadcasting councils and the ZDF Television Council). It is no coincidence that their dysfunctionality – an attribute it is worth naming from the outset – gives rise to the debate on the broadcasters’ credibility. Thanks to the license fee, these broadcasters have the opportunity to conduct truly independent research and to offer programming that is diverse, critical, separate from the state, and independent of viewing figures, and aims to be relevant. Adherence to the programming mandate, as set out in the state treaties of the states and the State Media Treaty, must be monitored by the supervisory bodies. The lack of monitoring by the bodies responsible in some cases gives rise to the question of how their members are appointed and which organizations contribute members. The answer is often a call for the bodies to be more representative of the population.

A pioneering ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court stated that the councils are missing precisely this representativity, found that – specifically for the ZDF Television Council – policymakers were too dominant, and called for reform (BVerfG, 1 BvF 1/11 dated 25.3.2014). But what does representativity mean and how can it be implemented? At first glance, it seems anachronistic for a group like the exiles’ lobby to be sending representatives. But looking at the question from the other side – which organizations should be represented? And how can the dynamic development of society be reflected?

This results in a fundamental question: Does making the membership of a body like this more representative and diverse improve monitoring of whether the programming mandate is fulfilled? Or: Is this absolutely necessary? Diversity research shows that a diversity of perspectives, such as through differences in origin, gender, age, etc., leads to a better work result because the considerations made are more comprehensive and less stereotypical.

Particularly where guidelines are more abstract, having a rich range of perspectives benefits the configuration and implementation described above. It may therefore be worth considering more diverse options for membership of supervisory bodies. This makes it necessary to determine the status quo in relation to membership of supervisory bodies in PSM. That is the objective of the investigation below – which also unearthed various other interesting findings.

2. Principles and investigations into efforts to achieve diversity

Answering the fundamental research question – the extent to which the composition of the ARD broadcasting councils and the ZDF Television Council reflect the diversity of German society – requires a reference value with which the data and results collected can be compared. To make this comparison easier, the data and results are categorized (see below). The data was collected not by the study’s authors themselves, but in surveys by other bodies (e.g., Destatis).

While the (lack of) diversity in the programming offered by the broadcasters is often discussed, there is little criticism in societal discourse of the plurality and diversity of appointments at the broadcasters. As of 2022, all public service broadcasters had signed the »Diversity Charter« – although this is merely a voluntary agreement with no supervisory mechanisms (cf. https://www.charta-der-vielfalt.de/) and has no influence on the broadcasting councils, since the members are not appointed by the broadcasters themselves.

Marie Mualem Sultan (2011) describes the current state of research as an »interface of two [insufficiently] illuminated fields of research. […] Questions have so far been researched en bloc only insufficiently and sometimes […] not at all« (Sultan 2011: 21). There have been investigations into diversity for other sectors, but these are not currently focused so comprehensively on the characteristics of all committee members (Rieck/Bendig/Hünnemeyer/Nitzsche 2012). The investigation by the group Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen in July 2022 looks at the supervisory bodies of the public service broadcasters. Entitled »What society is that supposed to reflect?,« it establishes a lack of diversity and an imbalance in the membership of individual broadcasting councils, combining the results with interviews with experts and those affected regarding potential for improvement (Goldmann 2022). The study’s authors are clear that the situation needs to change. But what are the methodological difficulties in categorizing committee members whose data is not available in standardized form and who are as multidimensional as any person?

3. Analysis and interpretation

At the time of the analysis (key date: December 28, 2021), there were 473 people in the ARD broadcasting councils and the ZDF Television Council. Any deputies of the members who entered the councils after this date were not included in the investigation. The figure includes five people who are not publicly named and positions that are not filled; these are not included in the percentages below. (Exception: where categorization was possible even without a name, for example in the case of government representatives, which were also counted as »politically organized« council members.) To allow the variety and diversity of the committees to be evaluated, investigation categories were formed, largely based on the Diversity Charter.

Table 1

Categories

Source : Authors’ own illustration

The outside level of the Diversity Charter looks at company-related factors that were not relevant for the investigation into broadcasting councils. Other factors describe characteristics that cannot be determined and evaluated through objective research conducted purely digitally, without personal contact with the people in question.

In general, research into the individual council members highlighted a major problem with transparency. Very few broadcasters provide profiles or information on council members that go beyond a list of names. A lot of information and profile data therefore had to be drawn from a wide range of sources, and some was impossible to find due to a lack of online presence.

In this investigation, council members were only categorized as having a migration background or disability where this was explicitly stated or became clear through research. The intention behind recording the »geographical location« in the investigation was to examine whether there were any hotspots (e.g., overrepresentation of Munich in Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR)’s Broadcasting Council) or an urban-rural discrepancy. As it was not possible to determine a main place of residence, this category was not included in the analysis.

Because the federal structure results in a very high number of different associations and institutions, the individual organizations are examined together in overarching categories. In many cases, it was also impossible to determine the marital and family status. Since conclusions drawn on this basis would be invalid, these two categories are omitted from further examination in the analysis. The same problem was encountered when it came to classifying political attitudes.

Further information needed in order to understand and assess the investigation can be found below. Percentages in the charts are rounded for simplicity.

3.1 Analysis criteria and analysis

Gender

The gender distribution in Germany shows a slightly higher proportion of women: 50.68 % compared to 49.34 % men (cf. Federal Statistical Office/Destatis 2022). There is no reliable data on how many people in Germany describe their gender as ›diverse.‹

None of the committees investigated have members who describe themselves as non-binary. The gender ratios in the broadcasting committees vary, with trends in both directions. In total, however, the gender ratios in the broadcasting councils are dominated by male members: 269 men compared to 199 women.

The queer community’s interests are only visibly represented at RB, WDR, SR, and ZDF. Representation of women is better, with only the ZDF Television Council not having a women’s representative. The greatest discrepancy from the demographics of society as a whole is seen in the Broadcasting Council of Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (mdr), 86% of whose members are men. In the ZDF Television Council and the rbb Broadcasting Council, too, more than two thirds of the members are men. Only the supervisory bodies of Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR), and Hessischer Rundfunk (hr) have a female majority.

Figure 1

Gender

Source : Authors’ own illustration

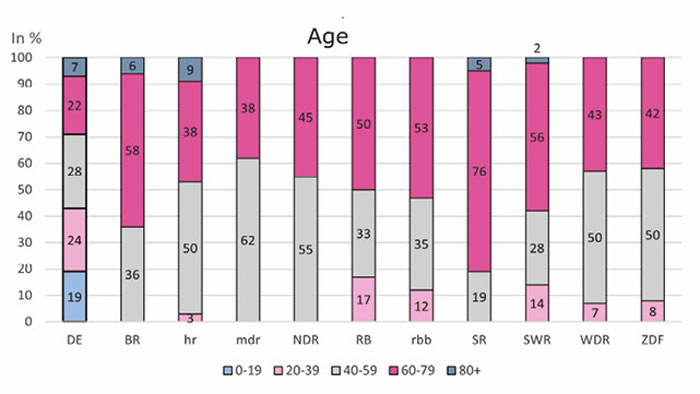

Age distribution

The largest group in Germany, numbering 23.07 million people (27.7%), is the 40 to 59-year-olds, followed by the 20 to 39-year olds (24.4%) and the 60 to 79-year-olds (22%). 15.43 million people, or 18.6% of the total population, are under 20 years old (cf. Federal Statistical Office/Destatis 2021b). On the date in question, the mean age on the broadcasting councils was 59 years – significantly higher than the mean age of the population as a whole (44.6 years). There were 115 people for whom no age could be determined.

The investigation shows that not a single council member is younger than 21 years. Just 23 of the more than 400 representatives are in the 21 to 40-year-old category. The majority of the council members are in the age ranges 41-60 years and 61-80 years, although the representation of the individual age groups varies between the committees. However, the discrepancy in the mean ages of the councils and the population as a whole is immediately clear in all.

The Broadcasting Council of Südwestrundfunk (SWR) is the only one in which four of the five age categories are represented, albeit in different proportions from the population as a whole. The NDR committee is comprised solely of representatives of the dominant age groups, with people aged under 40 and over 80 not represented at all. The councils of Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR), Hessischer Rundfunk (hr), Saarländischer Rundfunk (SR), and Südwestrundfunk (SWR) all have members over 80 years old.

The group of 60 to 79-year-olds provides the majority in several committees, including the councils of BR (58%), rbb (53%), and SWR (56%). At RB, this age group accounts for exactly half; at SR, it provides more than two thirds of the members. The 40 to 59-year-old age group provides half of the members of the ZDF Television Council, as well as of the hr and WDR Broadcasting Councils. In the mdr and NDR committees, they make up the largest age group at 62% and 55%. The two youngest representatives are 21 and 24 years old. Two of the youngest ten sit on the Broadcasting Council of SWR; three on the WDR Broadcasting Council. Three of the oldest ten each belong to the committees of Hessischer and Bayerischer Rundfunk. The two oldest are 85 years old.

With a mean age of 66 years, the SR Broadcasting Council leads the table in the age analysis.

Migration background

According to the Federal Statistical Office’s definition, 26.7% of people in Germany have a migration background (cf. Federal Statistical Office/Destatis 2021a), meaning that they or at least one parent was born with non-German citizenship. None of the councils have a rate anything like as high as this figure. The closest in terms of ethnic diversity is the hr Broadcasting Council, 13% of whose members have a migration background. It is followed by the committees of SWR (11%) and BR (8%). Neither Mitteldeutscher nor Saarländischer Rundfunk provided any indication of a representative with a migration background. However, migration/integration organizations are represented in all committees apart from the mdr Broadcasting Council. More detailed differentiation (e.g., by generation, reason for migration, or country of origin) is not possible.

Figure 2

Age

Source : Authors’ own illustration

Figure 3

Migration background

Source : Authors’ own illustration

Disability

Another relevant figure and key factor in diversity is the rate of disability. In Germany, 9.4% of people are categorized as having a disability (cf. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes 2020).[2] Here, too, there is a clear discrepancy between the proportion in the broadcasting councils/Television Council and the population as a whole. Barely a single council member has a disability, or has publicly stated so. Only the councils of Bayerischer Rundfunk, Norddeutscher Rundfunk, Radio Bremen, Südwestrundfunk, and ZDF have members who provide information on impairments.

Figure 4

Disability

Source: Authors’ own illustration

At this point, it is important to note that it was not possible to check the type and severity of the disability. It is therefore not clear whether the council members in question have classified themselves as having a disability or carry an official disabled person’s pass [Schwerbehindertenausweis]. In addition, there is no visible differentiation between certain types of disability, even though the type and extent have an enormous impact on the very different needs for accessible services.

Organizations for people with disabilities are represented in only half of the committees investigated. There is no congruence between broadcast area and associations. This is seen particularly clearly in the example of the ZDF Television Council, which is responsible for all of Germany – the interests of people with disabilities are represented here by the group »Inklusive Gesellschaft aus dem Land Rheinland-Pfalz« [Inclusive society from the state of Rhineland-Palatinate].

Religion

According to a study on confession and religious affiliation, 26.9% of the German population consider themselves atheist or agnostic, i.e., »non-believers.« 64.3% of the population is Christian, divided into 28.6% Catholic, 25.8% Protestant, 2.2% Orthodox, and 7.6% other Christian denominations. Another 3.5% of the population consider themselves Muslim, 0.7% Buddhist, and 0.1% Jewish (cf. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung 2020). Since it was not possible to ascertain the religious affiliation of all council members, the statistics must be enjoyed with caution. Despite this, the category was still included in the analysis because the clear discrepancy between the demographics of Germany and those of the councils has repeatedly been the subject of discussion.

Analysis in this category is especially challenging given that here, too, many committee members have not made their religious affiliation public. In these cases, it was therefore impossible to determine with any certainty whether these people consider themselves atheists or similar, or simply prefer not to state their confession. It is also difficult to consider the Christian denominations (predominantly Catholic and Protestant in Germany) in more detail, given that there are significant differences depending on geographical location.

It is striking, however, that the percentage of Christians in the councils is lower than the mean for Germany as a whole. The proportion of Muslims in the council – 2.56% to 3.33% – is slightly lower than in the population as a whole, with five councils having no visible Muslim representation at all.

Members of the Jewish community are found on all committees (1.67% to 4.65%) except the broadcasting councils of Radio Bremen (RB) and rbb. Their percentage share is slightly higher than that of Jews in the population as a whole.

Table 2

Religion

In absolute numbers. Source: Authors’ own depiction

</ br>

In percent. Source: Authors’ own depiction

Highest educational qualification

28.6% of the German population have achieved a lower secondary school certificate [Hauptschulabschluss], 6.5% a certificate from a polytechnic school (GDR), 23.5% a higher secondary school certificate [Realschulabschluss], and one in three (33.5%) a university entrance qualification. 4% have no school certificate at all. Formal educational qualifications are distributed as follows: 46.6% have an apprenticeship/professional training, 8.4% a qualification from a vocational college, 2.6% a bachelor’s degree, and 1.8% a master’s degree. University diplomas »[including] a teaching qualification, a state examination, Magister, artistic qualification, or comparable qualification« are held by 12.86% of the German population (Federal Statistical Office/Destatis, 2019, p. 22). 25.2% have no professional qualification.

The investigation into broadcasting councils always shows only the highest educational qualification. This means that, for example, the value Abitur [university entrance qualification] was only assigned if no further education or training could be found for the person in question. Council members with degrees were assigned the value of their qualification, rather than Abitur, as this is generally a requirement for a degree program. The value Degree includes those who did not provide more precise information,[3] while the number of bachelor’s degrees etc. is not taken into account, but listed separately.

21 council members stated that their highest educational attainment was a school certificate (of these, seven a higher school certificate, 13 a German Abitur, and one a university entrance qualification attained outside Germany). Nine had completed a (professional) apprenticeship. 112 members went to university, but did not provide the subject or type of qualification. There are also numerous council members with a bachelor’s or master’s degree, Diplom, Magister, or state examination. 63 council members have a doctorate, and 22 have completed postdoctoral studies. All in all, that totals 303 people with an academic career, making up a 47% share – rising to 65% when doctorates and postdocs are included. That is a major difference compared to the proportion of people with degrees in the population as a whole, which is just 17.3%.[4]

Table 3

Professional/educational qualification

In absolute numbers. Source: Authors’ own depiction

</ br>

In percent. Source: Authors’ own depiction

Political background

The PSM and their committees are often criticized for being too close to the state (see various rulings on broadcasting by the Federal Constitutional Court in the past, e.g., BVerfG, 1 BvF 1/11 dated 25.3.2014). This has resulted in rules on the maximum number of government ministers, employees, and parliamentarians. Because political affiliation and therefore influence is not always tied to one of these functions, however, the council members were investigated for possible political connections. In this investigation, »politically organized« refers to any person who is or has been a member of a party. Again, only official and public information could be taken into account.

In total, the councils contain 131 people with a clear political background, making up a 28% share. Information on the party affiliations of individual members can be found in the analysis of individual council members (see Excel sheet). Clear classification was not possible in all cases (due to a lack information or a change in party, or because a party affiliation is unrelated to the reason for appointment to the supervisory body).

Associations

Germany’s federal system means that groups with the same interests and agendas are often found in a huge variety of organizations and under different names. It is therefore impossible to examine every association, but a detailed list can be found in the analysis of the investigation (see Excel sheet).

In order to still draw conclusions from the data set, the associations were divided into overarching categories. It is clear that political organizations are the group most commonly represented, followed by culture-related associations, unions, and social organizations. The Christian congregations are found in fourth and fifth place in the list (without taking their political lobbies into account). Although media professionals (e.g., journalists) also sit on the decision-making committees, association representation by, for example, the Deutscher Journalistenverband (DJV) or the Deutsche Journalistenunion (dju) (part of the Verdi union) is rare.

As the disability category showed, there is no comprehensive, nationwide lobby for people with disabilities in the broadcasting councils or the ZDF Television Council. People with a migration background have organized representation in all broadcasting councils apart from that of mdr. hr, BR, SWR, and rbb all have a lobby for exiles, although many of these associations cater only to exiles from Eastern Silesia – there are no lobbies for other resettlers, such as those from German-speaking areas of Transylvania in Romania, most of whom came to Germany after 1990). While rbb and mdr jointly offer Sorbian programming, only rbb appears to have an organized lobby for this group. The Broadcasting Council of Radio Bremen also has a representative of the »Bundesrat för Nedderdüütsch« [Federal Council for Low German].

Table 4

Affiliation to organizations

In absolute numbers. Source: Authors’ own depiction

3.2 Interpretation of the investigation results

There is no discernable proportionality between the number of members in a council and the area or population of the respective broadcast area. The Broadcasting Council of SWR is the largest with 74 members, even though it is only responsible for two states (Baden-Wuerttemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate). Even the ZDF Television Council, whose role is nationwide, has only 60 members. The smallest Broadcasting Council is rbb’s with 31 representatives.

When it comes to gender distribution, the councils vary widely in their representativity. While the Broadcasting Councils of hr, BR, and SWR have balanced representation of men and women, in line with the demographics of men and women in Germany, NDR and WDR have a higher proportion of women, with seven and eleven women more respectively. The opposite applies to the ZDF Television Council, which has 42 male members, accounting for a 72% share, compared to just 17 female members – a share of just 28% or less than a third. The average age for both male and female members of broadcasting councils is 59 years. In the demographics for Germany as a whole, 43% of citizens are less than 41 years old. However, this age group makes up just 2.1% of the councils (10 people). Most of the council members are in the 61 to 80-year-old age group, making up 34.7% of the committees, even though their share of the total German population is much lower, at 22%. One possible reason for this is that membership of a broadcasting council is a voluntary position that may not always fit in with paid work. Yet it is still striking that neither NDR nor mdr has a single member who is younger than 41 years old (see also Fig. 2).

While 26.7% of people in Germany have a migration background, the same can be said of just 5.7% of broadcasting council members. The discrepancy in the representation of people with disabilities is even greater, with just three council members stating that they have a disability. Where associations are included, there is at least representation for disabled people in six of the ten committees investigated: BR, RB, rbb, SR, SWR, and WDR. Given that just under one in ten people in Germany has a disabled person’s pass, this level of representation is difficult to justify from a quantitative point of view. It is made worse by the wide range of different types of disability – after all, a person with a hearing disability has entirely different requirements of public service broadcasting than someone with autism. The lack of perspectives of a wide range of groups in need of assistance must be viewed particularly critically, because a lack of accessibility cannot be detected by those not affected to the same extent as by those affected.

Some other groups of people also appear underrepresented. Although 8% of Germans consider themselves queer, for example, their proportion in the broadcasting councils is just 0.63% with three organizations represented (in RBB, MDR, and the ZDF Television Council) – many times lower than the value/share for the population as a whole.

25% of council members stated that they had Christian beliefs, with a clear majority in all councils. This is a deviation of 39 percentage points from the figures for the population as a whole. There are two potential reasons for this phenomenon: Firstly, many members of broadcasting councils did not publicly state their religion; secondly, a difference can be expected between those who belong to a church in the statistics and those who actively consider themselves believers. Although only four council members stated Islamic beliefs, the percentage across all committee members is largely consistent with that of the population. However, there are some committees in which Islam is not represented at all. It is a different picture when it comes to Judaism: The councils have a total of 10 Jewish members, making up a share of 2.1%, while Jews make up just a 0.1% share of the population as a whole. No other religions are represented, with the exception of one Alevite.

One striking feature is the high percentage of politicians compared to other professional groups, with 28% having close links to politics or a political party. People with a connection to the church or other religious groups (9.3%) are also strongly represented, followed by media professionals and members of the legal professions. When it comes to how the politicians are spread across the parties, the picture is largely consistent with the (longer-term) political situation in Germany. The largest group is the CDU (Christian Democratic Union) and CSU (Christian-Social Union in Bavaria), with 50 and 13 council members respectively. This is followed by the SPD (Social-democratic Party of Germany) with 50 members, and Greens with 20 council members, and then Die Linke and the FDP (Free Democratic Party). The AfD (Alternative for Germany) comes in sixth place, with six representatives.

The large proportion of council members with a university entrance qualification and academic career is also striking. Only a handful can be categorized as »working class,« although trades unions are certainly also represented.

It is not possible to evaluate how many council members are parents. This is due to the problem that demographic figures assume current parenthood, but do not count the total percentage of citizens who have children. The data available for research on this point was also insufficient, as many did not provide this information. As a result, it is impossible to prove definitively whether they actually have no children or simply do not want the information in the public domain. It is a similar story when it comes to information on marital status. 183 council members are known to be married, making up a 40% share of all committee members. The lack of public availability of information – not to mention the importance of maintaining the privacy of members of broadcasting councils – also made it impossible to investigate other interesting categories in the Diversity Charter (such as sexual orientation). More detailed differentiation was also impossible for the same reason. Figures on characteristics like single parenthood, receipt of out-of-work benefits, urban or rural residence, BGO activities etc., could provide information on how diverse the perspectives in the councils are.

3.3 Methodological critique

Quantitative content analysis is essentially a useful way to determine the diversity of the councils of public service broadcasting, allowing individual members of the respective committees to be investigated for diversity characteristics. Qualitative evaluation can also be reasonably conducted based on categorization in order to provide comparability, although the choice of categorization demands classification. On its various levels, the Diversity Charter names criteria intended to create a staff that is as diverse as possible. The problem is that, since there is no precise definition of how the categories should be defined, there is room for interpretation.

Another point of criticism relates to the object of research itself. All of the information categorized and analyzed is the result of extensive online research; much of it could not be found as a primary source. It is therefore impossible to guarantee that the data is absolutely up to date, as the information provided may be out of date. Neither is the data complete. Although it was possible to research data on many of the council members, information on those council members who are less well known and not public figures was harder to come by. Given these gaps in the data set, it is possible that individual figures and evaluations may not be correct. In a repeat investigation, this inaccuracy could be minimized by using different methods of procuring information (for example a questionnaire).

4. Summary

Public service broadcasting is an integral part of the German media landscape and a key factor in our democracy. Yet this ideal is confronted with the finding that the work of the supervisory bodies is frequently inadequate. There are various structural reasons for this. As the recent debate about internal press freedom, extending to NDR, mdr, and WDR, shows, there is a need for reform in the Director Act (Intendantengesetz), the rights of co-determination of employed staff and freelancers, the pension fund that eats up funds for programming, the restructuring and synergy formation at the individual institutions, the digitalization and work of the supervisory bodies, and their facilities in the committee offices. The diversity of perspectives in the broadcasting councils undoubtedly plays a role when it comes to the programming mandate and the diversity of programming. This work focused exclusively on the broadcasting councils of the individual ARD institutions and the ZDF Television Council, as these are intended to guarantee that these broadcasters fulfil the role they are assigned in the state treaties and the quality standards expected. Firstly, it is important to note that, for a long time, very little research was conducted in relation to the broadcasting councils. Even after this work, it is impossible to provide a simple answer to the question of how diverse and representative these committees are compared to the population as a whole. This investigation is only a fraction of the possible research and shows that there are sometimes enormous differences between the individual councils, and therefore both positive and negative examples, when it comes to diversity. What is obvious, however, is that there is a clear discrepancy from the population in the age, migration background, and disability categories especially, as well as overrepresentation of politics, and that the representation of interests is therefore neither sufficient nor balanced.

This investigation can be seen as a key part of research on the current status and opportunities for improvement in this regard, while also offering plenty of scope for more detailed questions and more precise investigations. One option would be to conduct a more sophisticated analysis of the entry requirements, so that groups that are underrepresented or not represented at all are given more opportunities to participate. It is also worth asking how the dynamics of society can be reflected in committees like this. In this context, one option would be to include audience representation on the councils – individuals elected by the public who are also appointed to the broadcasting committees and contribute to greater transparency, discussion, and debate on media issues. This would also give citizens who are not associated with particular groups the chance to help decide on the committee membership and ultimately, to some extent, to be involved in decisions made regarding directorships and other points, such as quality criteria for program critique. The respective state media treaties would have to be amended accordingly.

It is clear that this field of research is still not taken seriously enough. All public service broadcasters have signed the Diversity Charter. Effectively implementing these criteria in the staff and therefore also in the membership of the councils would be another step towards greater diversity, including of opinion and perspective. Despite having a different concept for research work and a different period of investigation, the study by Neue Deutsche Medienmacher*innen came to similar results and confirms the major trends in these results – focusing on the lack of diversity in the dimension of »migration background« –, thus reinforcing the finding that there is an enormous need for reform when it comes to diversity mainstreaming in the supervisory bodies of the PSM.

The context of digitalization presents all media with enormous challenges that can only be successfully tackled with a large number of ideas and solution approaches. Studies on the world of work (cf. Diversity Charter) show that diversity leads to better results at all levels. Public service media should make sure to use this advantage – indeed they must, given that their programming mandate relates to the entire population and must be free from discrimination. Diversity is not only a relevant factor in credible, high-quality media, but is also crucial to encouraging loyalty among the audience, who now have a great deal of choice and must make a conscious decision to choose a PSM program. Needless to say, it is essential that the bodies supervising the PSM’s services also demonstrate this inviting diversity of perspectives.

We would like to thank HMKW student Sophie Böse, who was substantially involved in the data collection and analysis.

About the authors

Jasmin Koch, Fabian Schöpp and Ronja Tabrizi are studying for a bachelor’s degree in journalism and business communications at the University of Media and Communication Frankfurt.

Sabine Schiffer is a professor at the Hochschule für Medien Kommunikation und Wirtschaft (HMKW) in Frankfurt am Main. Her work focuses on the relationship between the Fourth and Fifth Estate (i.e., PR and lobbying), stereotype research, and media education.

Translation: Sophie Costella

References

Arena, Amedeo; Bania, Konstantina; Brogi, Elda; Cole, Mark, D.; Fontaine, Gilles; Hans, Silke; Kamina, Pascal; Kevin, Deirdre; Llorens, Carles; Mastroianni, Roberto; Petri, Michael; Wojciechowski, Krzysztof; Woods, Lorna (2016): Medieneigentum: Marktrealitäten und Regulierungsmaßnahmen. Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle.

Blum, Roger (2022): An ideal hobby garden (for me) Communication studies’ forays into media regulation. In: Journalistik/Journalism Research, 5(3), pp. 290-298. https://journalistik.online/en/essay-en/an-ideal-hobby-garden-for-me/ DOI: 10.1453/2569-152X-32022-12699-en

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (2020): Soziale Situation in Deutschland – Religion. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/zahlen-und-fakten/soziale-situation-in-deutschland/145148/religion (4 November 2022)

BVerfG, Urteil des Ersten Senats vom 25. März 2014 – 1 BvF 1/11 -, Rn. 1-135. http://www.bverfg.de/e/fs20140325_1bvf000111.html

Freienvertretung des rbb (2022): Nicht mehr ohne die Belegschaft! https://www.rbbpro.de/blog/2022/08/24/resolution-der-rbb-belegschaftsversammlung (4 November 2022)

Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes (2020): Schwerbehinderte Menschen u.a. Nach Geschlecht Grad und Ursache der Behinderung. https://www.gbe-bund.de/gbe/pkg_isgbe5.prc_menu_olap?p_uid=gastg&p_aid=2956184&p_sprache=D&p_help=2&p_indnr=216&p_indsp=&p_ityp=H&p_fid= (4 November 2022)

Goldmann, Fabian (01.08.2022): Welche Gesellschaft soll das abbilden? Mangelnde Vielfalt in Rundfunkräten und was dagegen hilft. https://mediendiversitaet.de/fileadmin/user_upload/20220803_Studie_Rundfunkraete_NdM.pdf

Grassmuck, Volker (o. D.): S.V. Öffentlich-rechtliche Medien. https://www.vgrass.de/?page_id=4028 (26 October 2022)

Hallin, Daniel C.; Mancini, Paolo (2004): Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790867

Klein-Schmeink, Maria; von Notz, Konstantin; Grundl, Erhard (2022): Öffentlich-rechtliche sind Fundament der Demokratie. https://www.gruene-bundestag.de/themen/medien/oeffentlich-rechtliche-medien-als-fundament-der-demokratie (4 November 2022)

Krüger, Uwe; Köbele, Pauline; Lang, Mascha Leonie; Scheller, Milena; Seyffert, Henry (2022): Inner freedom of the press revisited. In: Journalistik/Journalism Research, 5(3), pp. 228-247. https://journalistik.online/en/paper-en/internalfreedom-of-the-press-revisited/

Mualem Sultan, Marie (01.06.2011): Migration, Vielfalt und Öffentlich-Rechtlicher Rundfunk. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann.

Rieck, Christian; Bendig, Helena; Hünnemeyer, Julius; Nitzsche, Lisa (2012): Diversität im Aufsichtsrat: Studie über die Zusammensetzung deutscher Aufsichtsräte. Frankfurt/M.: Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences; Frankfurt Research Institute for Business and Law.

Robra, Rainer (o. D.): Medienpolitik in Sachsen-Anhalt. In: https://medien.sachsen-anhalt.de/themen/medienpolitik (26 October 2022)

Schiffer, Sabine (2015): Medien in Deutschland. Über den Zustand des Medienbetriebs. In: Thoden, Ronald (ed.): Wie Medien manipulieren. Frankfurt/M.: Selbrund Verlag, pp. 186–202.

Schiffer, Sabine (2021): Medienanalyse: Ein kritisches Lehrbuch. Frankfurt/M.: Westend Verlag.

Statistisches Bundesamt/Destatis (2020): Bildungsstand der Bevölkerung – Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2019 – Ausgabe 2020. Statistisches Bundesamt. In: destatis.de. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Bildungsstand/Publikationen/Downloads-Bildungsstand/bildungsstand-bevoelkerung-5210002197004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (4 November 2022)

Statistisches Bundesamt/Destatis (2021): Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund.Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2020. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/Downloads-Migration/migrationshintergrund-endergebnisse-2010220207004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (03 March 2023)

Statistisches Bundesamt/Destatis (21.06.2021): Bevölkerung nach Altersgruppen (ab 2011). In: destatis.de. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/liste-altersgruppen.html (02 November 2022)

Statistisches Bundesamt/Destatis (2022): Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht. Statistisches Bundesamt. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/zensus-geschlecht-staatsangehoerigkeit-2021.html (02 November 2022)

Statistisches Bundesamt/Destatis (o. J.): Migrationshintergrund. In: destatis.de. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Glossar/migrationshintergrund.html (28 December 2022)

Footnotes

1 It is impossible to talk of independence from the state when it is policymakers who decide the funding given to journalists. France must be said to have state media rather than a public service system. This is an enormous incursion into the freedom and independence of broadcasting, even if it is not yet particularly noticeable in the programming.

2 This refers to people who hold an official disabled person’s pass [Schwerbehindertenausweis]. This must be applied for and is issued from a disability level [GdB] of at least 50. The actual proportion of people in Germany with a disability is therefore higher.

3 The poor data available made it impossible to state whether the degree was completed successfully.

4 In addition, in describing and classifying his own experiences in Switzerland, Roger Blum clearly highlights the opportunities not exploited in the supervisory bodies, for example due to the failure to integrate communication studies expertise (cf. Journalistik/Journalism Research, 5(3), pp. 290-298. https://journalistik.online/en/essay-en/an-ideal-hobby-garden-for-me/).

About this article

Copyright

This article is distributed under Creative Commons Atrribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and redistribute the material in any medium or format. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. You must however give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. More Information under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en.

Citation

Jasmin Koch, Sabine Schiffer, Fabian Schöpp and Ronja Tabrizi: Representativity in broadcasting and television councils. A comparative analysis of the discrepancy between council composition and demographics . In: Journalism Research, Vol. 6 (1), 2023, pp. 32-54. DOI: 10.1453/2569-152X-12023-13026-en

ISSN

2569-152X

DOI

https://doi.org/10.1453/2569-152X-12023-13026-en

First published online

April 2023